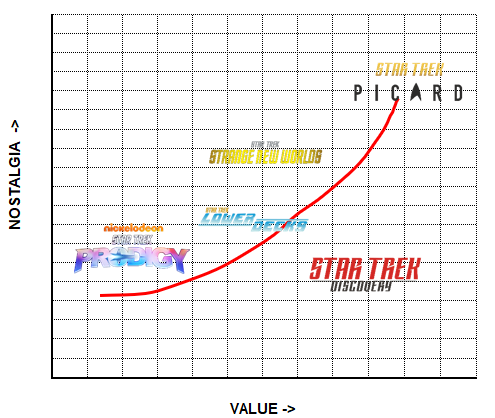

(Part 5 of the Nostalgia Curve. Click the numbers for Parts 1, 2, 3, and 4).

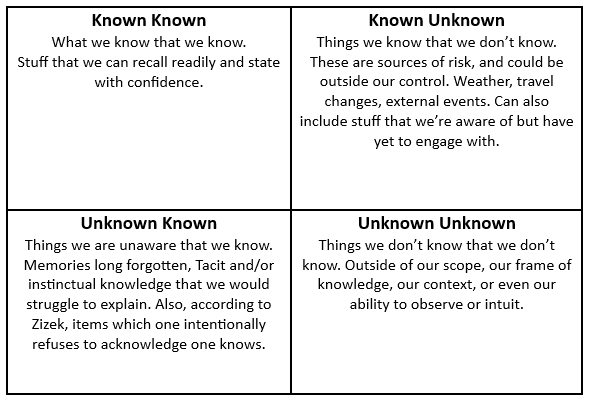

In February of 2002, then US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld introduced the wider world to the concept of “unknown unknowns” – those things that we don’t know that we don’t know. Adopting a framework familiar to those within the risk assessment fields, it was more the delivery of the idea that caused it to go viral and to stick. Uttered in a statement along with other elements of the type: known-knowns and known-unknowns, it flowed like something out of a Dr. Seuss book, and became instant fodder for the late-night comedians.

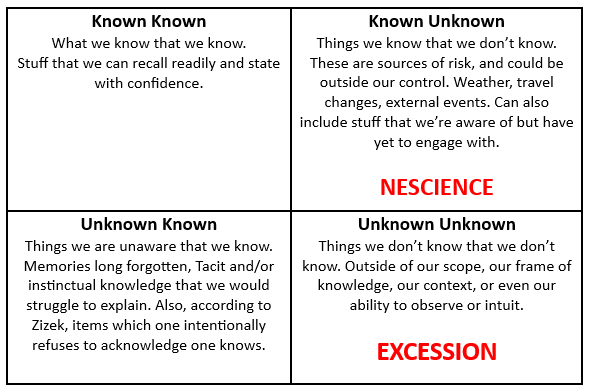

The full matrix looks something like this:

Laid out like this, it seems rather obvious. Now, Rumsfeld only mentioned three, and the philosopher Slavoj Zizek (among others) pointed out the missing fourth, the unknown-knowns (seen in the lower left quadrant). According to Zizek, these are “the things we don’t know that we know-which is precisely, the Freudian unconscious, the ‘knowledge which doesn’t know itself,’ as Lacan used to say.” But these are not without contention. The unknown-knowns can include the “the disavowed beliefs, suppositions and obscene practices we pretend not to know about, even though they form the background of our public values” according to Zizek.

Which, agreed, can be highly dangerous indeed.

But the unknown-knowns are a much broader category that Zizek intimates at. Unmentioned (or perhaps elided) are two great unknowns: tacit knowledge, and memory.

Tacit knowledge is that which we’ve learned but we struggle to explain. As Michael Polanyi states it: “we know more that we can tell”, and while this may seem to fit within the “known-knowns”, our struggle with verbalizing and explaining it, of bringing it forth into the world save through our actions hints at the “unknowing” part of its inclusion here. Memory, of course can sometimes be with us constantly, and other times the forgotten comes to the surface – sometimes triggered, oft unbidden – rushing like a flood.

And this gets to why I’m talking about this in the context of The Nostalgia Curve. Those seeking to evoke our nostalgia often key them to those unknown-knowns, those long forgotten memories of childhood – of toys and cartoons, of lazy Saturday mornings and long summer days – and seek to market them to an older, more mature, more gainfully employed audience of carefully diagnosed market segments. And there is a lot that has been written on nostalgia up til now.

It became obvious early on in writing the elements of The Nostalgia Curve that I needed to engage with Fredric Jameson. I had not, to this point, aside from in passing, in the way that he gets cited in other works I had read, but I had never engaged with his texts directly. It was a known unknown. I realized Jameson’s writing may have a significant impact on my work, so I wanted to get my own thoughts down, as they stood, before engaging with his work. To do so required an intentional act on my part, an act of nescience.

Nescience

Nescience is the lack of knowledge. Full stop. This contrasts with something like ignorance, which is the act of not knowing. But wait, you ask, wouldn’t your intentional act of not engaging with Jameson be better described as ignorance? Is that a gotcha?

Well, no. They’re similar, for sure, but nescience lacks the pejorative associations we have with ignorance. Nescience is the unknown, in this case both the known unknown that Rumsfeld spoke of above, and the unknown unknown – the thing that we don’t know that we don’t even know. Much of the mysteries of the universe fall within this category, for we are creatures, tiny and small.

Besides, nescience sounds better. Let’s lean into the poetic if possible.

So we’re adopting nescience to mean that act of intentionally not engaging with something, of something that we may have heard of in passing, but don’t really know.

By way of disclosure, some other things that I am nescient about:

- Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (as mentioned above)

- The Eternals

- Titanic (the movie, not the boat)

- Schindler’s List

- The Sopranos

- Lost

- Batman: The Animated Series

- and the list goes on…

Obviously I know of them, else they wouldn’t be on this list, and given their pervasiveness in popular culture, one would be hard-pressed to not at least have heard of the above titles. Everyone will have similar lists – there are more videos uploaded to YouTube every minute than can be seen in a lifetime. So we will all have gaps in our knowledge. Nescience in this case is the wilful act of not engaging.

However, having nescience cover the full range of unknowns – both the known unknowns and unknown unknowns – leads to a bit of a conundrum. How do we separate between the wilful unknown, and the truly unknown-unknown?

What happens when we encounter an Excession?

Excession

The Culture is a series of science-fiction books written by the Scottish author Iain M. Banks, on-and-off over 25 years. In it, it describes a galaxy-spanning post-scarcity society in which various AIs are full citizens alongside the other various biological creatures. Excession, published in 1996, is the fifth book on the Culture, perhaps my favorite book in the series, and one of my favorite books of all time. Within it, the AI minds that control the ships discover something completely outside their frame of reference, something from outside the known universe (perhaps?)

An Excession is an outside-context problem. It is more than simply a Black Swan event, it is by definition unknowable. It is the unknown unknown of the Rumsfeld Matrix we mentioned at the start of this post. And it is within this frame that I’m bringing it into use. (Possible spoilers for a nearly 30-year-old novel).

The appearance of the Excession in the story demands immediate reaction – what do you do when you run into something completely outside your reality? Further observation, marshalling of resources, outright flight, all these and more are options. But the big takeaway is that an outside context problem may be exactly that – so detached from the frame that the best solution is to just let it pass on by. Of course, the nature of an excession is such that one can’t know that, at least not at first. So it can act as an inciting incident for all manner of other things. The very presence of an excession changes the worldview, the context for everything that come after.

Welcome to a wider universe.

So with the ideas of Nescience and Excession, our version of the Rumsfeld Matrix looks a little bit more like this:

But, all this nescience only goes so far. At some point one must do their diligence and get to the work of engaging with the unknown.

So what does Jameson have to say about Nostalgia, and how (or would) that change what we’ve come to know about the Nostalgia Curve? We’ll investigate that, and share it with you soon.