(This was originally published as Implausipod Episode 51 on November 12, 2025.)

https://www.implausipod.com/1935232/episodes/17441045-e0051-tron-s

Welcome to the Implausipod, where we are looking at one of the more influential franchises in both cyberpunk and science fiction, as we use the recent release of Tron:Ares (2025) to look at the impact of the franchise as a whole – including Tron (1982) and Tron: Legacy (2010) – on the ideas and development of our virtual worlds.

Welcome to the grid player. No, Teddy Long is a guest hosting this week. No one is going one-on-one with the Undertaker. But we are going back to the early history of computing to one of the most famous ways in which it was visualized through to current conceptions of what the interaction between the real and virtual worlds might be like.

Long before the Matrix, a decade before the Metaverse, at a time when cyberspace was still being formed, audiences were introduced to Tron and its quest to understand what it’d be like inside the machine. With the recent release of Tron areas, let’s take a look inside the machine and see what the grid looks like now on this episode of the ImplausiPod.

Welcome to the ImplausiPod, a podcast about the intersection of art, technology, and popular culture. I’m your host, Dr. Implausible. In 1980, video games were rising in popularity with the Atari VCS selling in the neighborhood of millions per year. And while the standup machines in the arcades weren’t awful per se, the graphics on the home systems were pretty rough.

They didn’t have the capacity for allowing full motion video of animation in any meaningful way. So when a hot media company like Disney wanted to be cool and jump on the trend, the games themselves weren’t the best way to give that authentic Disney experience. Now, this would change in later years, but not for a while yet.

Lucky for them, a creator had been working on a property that might fit the bill. Stephen Lisberger had been inspired by the release of Pong in 1972. And in 1976 opened an animation studio to work on various projects. The story pitch that would become Tron was rejected by much of Hollywood, but Lisberger’s Alice in Wonderland-inspired story resonated with Disney.

The end result of the decision to produce and ultimately release that film ended up introducing an early idea of virtual reality to millions of people far more than were reading the sci-fi novels at the time, and created an enduring legacy, no pun intended, that has inspired countless other creators for over four decades. Let’s take a look at how that all came to be through the various Trons

Tron was released in July of 1982 to a large amount of fanfare, typical of a Disney movie, and it resonated with audiences. It presented a fantastic version of what life would be like inside a computer, and even if not everybody was grabbing a home PC just then. The early video game consoles like the Atari 2600 and Intellevision, and the soon to be released ColecoVision had captured the imagination of consumers and kids everywhere in North America at least.

Just don’t ask about what happened to the consoles in 1983.

As the reviews here on the ImplausiPod are more about impressions, we don’t really wanna spend much time rehashing the plot, but we’ll cover it quickly here for completeness. Flynn is a programmer or software engineer who used to work at a company called Encom, and in the process of hacking into the system ends up getting digitized and transported into the company’s main server within the system called the Grid.

Programs look like human beings and interaction within the system takes place on a symbolic level. Other creatures exist within the grid too, various subprograms and routines and utilities can look like vehicles or other features. Within the virtual environment, Flynn gets conscripted and forced to fight in some gladiatorial contests within the grid, and works alongside some fellow conscripts, one of whom is named Tron.

Lucky for Flynn, he designed some of the games that he was forced to play, so he has got a bit of insider knowledge, if not the cheat codes per se. Not that cheat codes were that big of a thing in 1982, but we’d start seeing more of them soon. He and others break outta the controlled areas of the grid and start finding their way into the underground where they attempt to fight the system.

Literally turns out that the master control program for Encom, the MCP has achieved a limited degree of sentience and is now diverting resources to furthering its own development. This echoes a lot of the current fears We now have about AGI in the media in 2025, and along with Terminator in 1984, and Battlestar Galactica of a few years earlier.

We have a general distrust of AI occurring in popular culture at the time. Of course, we talked a bit about that back in episode 29. Why is it always a war on robots? If you want to go check out that show in the archives, they’re still available for free. But, uh, back in the grid, MCP is talking with a version of Dillinger the corporate exec who stole Flynn’s work and ousted him, doing his bidding as a rather scary Vader esque figure named Sark.

He directs the more militant aspects within the system to hunt Flynn down, but he and Tron are able to eventually defeat MCP and return Flynn to the real world to be reassembled with only a blink of time passing. It created with multiple film techniques, including backlighting, rotoscoping, and using very innovative set design.

Tron is a very interesting film to watch. Even now over 40 years later, the story gets a little slow in spots, and I’ll admit that teenage me kind of falls asleep in the final third where we get a bit heavy on the exposition. Still, it’s an amazing visual trip and continue to influence generations of future creators.

Tron ended up making about $50 million on its $17 million budget. A modest hit at the time, despite some common misconceptions now that it was a flop. The film was lauded for its technical achievements, nominated for Oscars for costume and sound. But the most amazing thing is that it was denied an opportunity to compete for visualist effects Oscar.

The limited computer generated imagery included in the film was considered Cheating. It almost seems laughable now considering how basic the CGI was at the time. And almost every film available uses something similar to that effect. But, uh, after release at the beginning of the home video era, the primary way to continue participating with the Tron universe was to engage with the video games.

The various scenes and mini games within the movie had an enduring appeal, easily translating to the video game arcades. The disc battle got its own standup, but the first Tron standup provided a selection of many games, each of which the player would have to defeat to progress, working through the cycles, tanks, the weird spider level thing, and eventually up to facing MCP in a version of Breakout.

I recall the game being frustrating because of the controls more than the game itself. Struggling with interface issues. Still it had always got a few of my quarters before I went back to playing Galaga and BattleZone for the afternoon.

Audiences re-entered the grid almost 30 years later in 2010, where Tron Legacy reappeared almost from nowhere almost because as a property, it seemed oddly untouched for the twin eras of dot coms and Matrix movies. But between those and the rise of smartphones and social media plans to revisit the franchise finally got underway, and this motion started surprisingly with a large number of players from the original movie still on board.

Steve Lisberger, the script writer and producer of the original came back as producer and Bridges and Boxleitner revise their roles as Flynn and Tron respectively. Filming got underway in 2009 and in late 2010, Disney released a modern version of Tron where the visuals could finally match the creator’s vision, buoyed by the very developments of tech that they inspired three decades prior, and the visuals truly did match.

Though in line with the state of the art of 2010 where we have reached the point with digital production that anything dreamed of can be brought to life on screen through special effects. In the story of Tron legacy, the audience is introduced to Sam Flynn, a young impetuous daredevil and hacker, an heir to the Encom Corporation, occupying a board seat he chafes at.

Flynn the younger visits his father’s old arcade and finds his body digitized in much the same way his father was decades earlier, and soon needs to compete within the the Grid and uncover the larger plot going on. The visuals in the movie are amazing, as CGI has massively improved in the intervening decades,

so the film didn’t need to engage in all the filmic techniques or animation of the original in order to bring the vision to screen. There’s some places where the CGI falters, like in the de-aging and face-mapping of Jeff Bridges onto Clu, but even here it represents a point in time and gave graphics capabilities that link it to the first movie.

And Clu introduces us to one of the more unique ideas in Tron Legacy, that of a digital double, an autonomous version of oneself within cyberspace, or in this case, the Grid. Of course, unlike the digital doubles created by the likes of Facebook and Google, for the purposes of more effective marketing and commodification, Clu has an agenda, wanting to destroy the ISOs, the naturally occurring isomorphic algorithm life forms of the grid.

He has also brought Flynn the younger to the grid so that he can escape to the real world and continue his quest for domination there. Perhaps it’s in the ideas where Tron Legacy falls a bit short, with the war between Clu and the ISOs, these ideas of digital natives different than the way the term is used for Millennials and Gen Z have been around for a while, showing up in mid eighties cyberpunk and ShadowRun source books long before they appeared in the Matrix and elsewhere.

There’s been a long association that creepy pasta exists on the fringes of the frontier and the digital frontier is no different. Tron Legacy is true to the title, repeating many scenes and story beats from the original, albeit in shinier high-definition forms, from the entry into the grid to the game arena, to the light cycles and subsequent, uh, escape into the frontiers of the grid to the sail, ship, escape, and recognizer.

The story beats hold much in common with the original. In addition to the visuals, though, the music is fantastic provided by Daft Punk to great effect. I gave the film a rewatch while working on this episode, as I hadn’t seen it since its release, and I was kind of left flat while watching it. Not 2D Flat, I’m still fully 3D rendered, but you know, I wasn’t as excited by it.

I think perhaps that’s part of the problem with Tron Legacy. It links to the story of the original, but it looks like any number of other sci-fi films of the early 2010s. The iconic elements of Tron still shine through the action in the grid, feels somehow weightless and transitory much like the Sprites themselves.

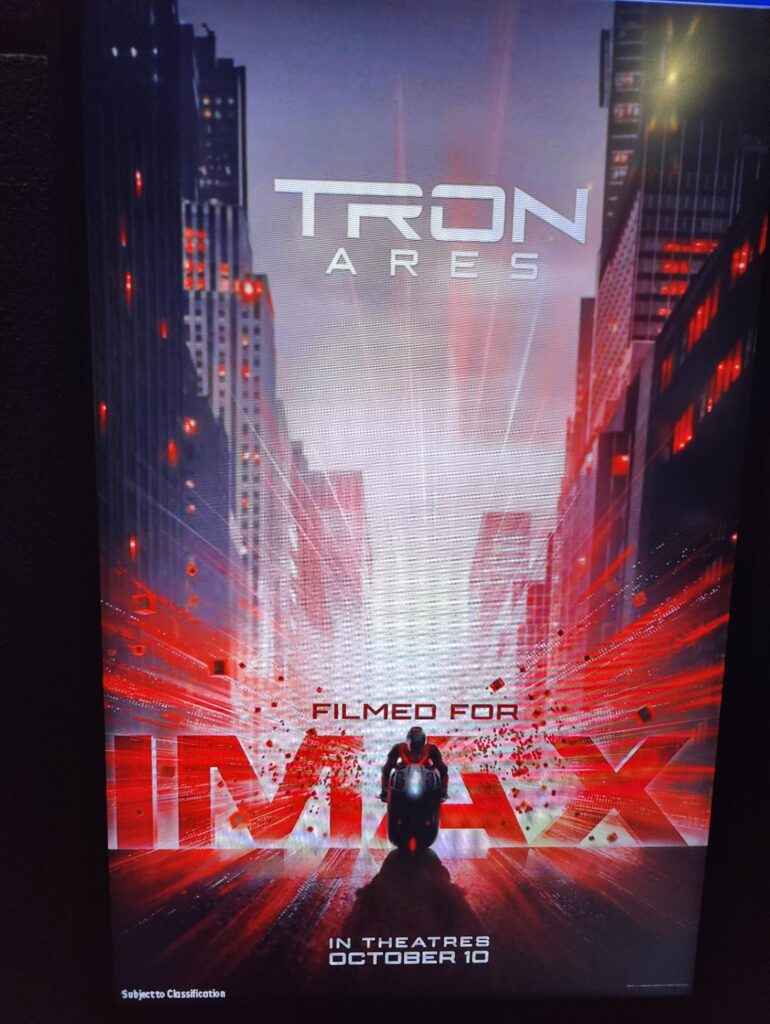

And in 2025, we returned to the grid once more as Tron Ares was released in early October of that year. With Tron Legacy doing reasonably well in the box office, grossing 409 million on a budget of one 70. It seemed a little odd that it took 15 years to get another sequel released, but there were production issues, which led to a reworking of the franchise, and then external impacts including both COVID and union related job action.

Tron Ares represents a bit of a shift as the software corporations of the earlier films are now in full competition to bring the digital realm into the material world, to merge cyberspace and meatspace, as it were. And much of the film revolves around this while following some of the story beats of the first two flicks.

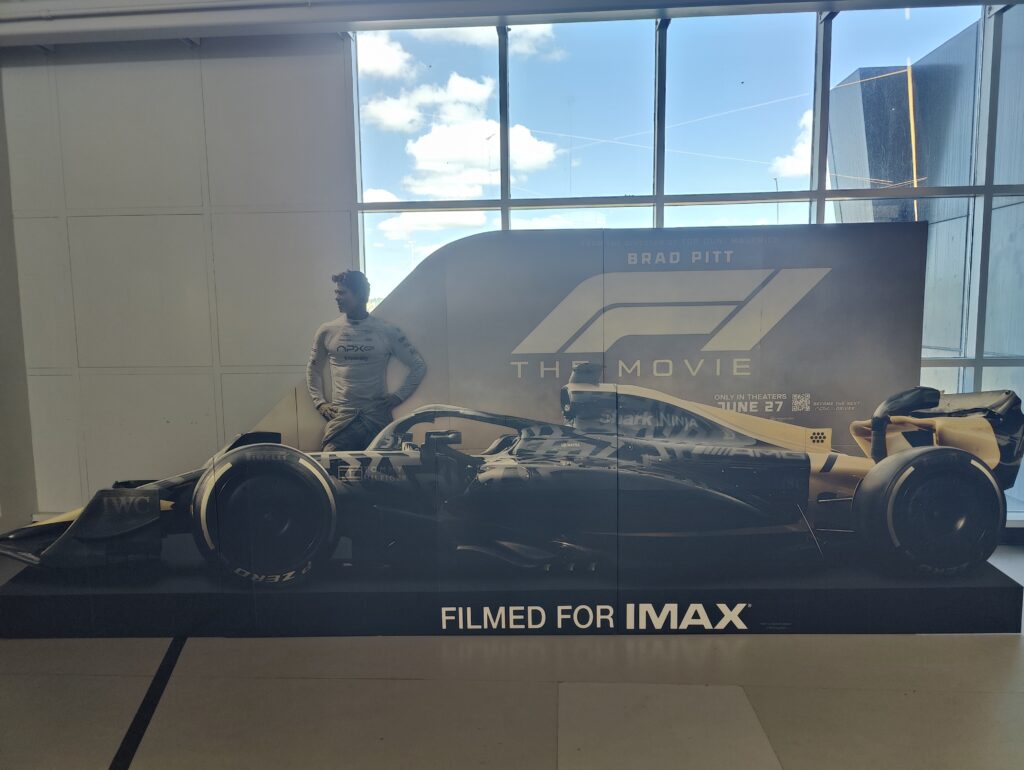

I recorded some quick thoughts after viewing the film in IMAX, as I was starting to see that the internet film community was telling me it’s a bad movie in ways that I clearly don’t agree with, so let’s talk about what I liked about the film. The graphics were hyper-stylized in a way that felt was an homage to some of the sci-fi of the seventies and eighties and in that way had a much stronger connection to the original Tron film.

A lot of the work in that film used costuming and odd camera angles and set design to imagine the insides of the computer, and this was a return to form. The ladder sequence during Dillinger’s hack was wild to me, a conceptual view of cyberspace agents and IC in choosing countermeasures that felt straight out of a cyberpunk novel in the late eighties or nineties.

It’s hard for me to express how much I love this bit and the style that it had. Similar was the return to the set pieces of the original Tron, which are recognizable and felt, for lack of a better term, low res, despite being rendered on the IMAX screen along with the rest of the movie, simpler, fewer things going on in the background, feeling like an early 3D rendered video game.

As for the tech, it took me a minute to come around as I originally thought the constructs bursting out of the familiar black carbon supports was a little goofy perhaps, but I came to like it, and it definitely had an aesthetic to them. It left a bit to the imagination of what constitutes the objects.

Are they holograms or built out of raw carbon? In other elements, it was left undefined, and that’s okay. Really, we were allowed to hand wave some stuff in a sci-fi to prevent it from bogging down the story. That being said, I found this approach to addressing the question of digital materiality really interesting.

Digital materiality is that point where the virtual crosses over to the real world. If cyberspace happens at the point of connection where a telephone conversation takes place in the wires, then digital materiality is where our 3D construct will cross over into real space or meat space, or objective reality, or however you wanna frame it of the characters.

Athena was very effective in the film. I really liked her as a character, echoing our fears of current real world implementations of AI, taking a command too far. She quotes “by any means necessary” to disastrous consequences for Dillinger. The character of Ares is an AI gaining emotional intelligence, by doing the deep learning on the target of Eve Kim presents a different way.

This EQ was what triggered his malfunction, but also pointed towards an avenue for growth for the AIs. Regarding Ares as a construct in the real world. It’s interesting as he’s clearly quote unquote, not human, despite having a human form, he’s a construct of whatever underlying form that takes that doesn’t just decompose.

We’re not given any indication that it is actually modeled after a human aside from its outward appearances. This provides a nice contrast with the various forms of post humanity seen in the recent Alien Earth Series, for example, where we had synthetic cyborgs and hybrids in various shapes and forms.

Ares represent an AI embodied within a synthetic body, more akin to the synths of Ash, Bishop and Kirsch, but with significantly enhanced capability. Ares in the real world is different in this way than the scanned and reassembled Eve Kim, whose reconstituted body theoretically does not have this problem of permanence.

Though it’s interesting to ask, why not? But one can follow that her rebuilt body is her being reconstructed cell by cell. It’s much like the Teletransportation paradox from philosophy, but also from Star Trek as to whether the original body is destroyed and then rebuilt here. The movie answers it with a clear yes, though with more intervening time in between.

The ending leaves open the possibility for further exploring what it’s like for an AI to experience the world materially in a way that is just hinted at in the postcard sequence from Ares. There’s room for some growth here. And finally, I like how they portray the uses for 3D printing technology with the permanence code enabled, combating climate change, medical advancements, et cetera.

A really hopeful version of the future, and less dystopian than similar films like The Matrix and Terminator. And overall I enjoyed the film. There was no prior knowledge of the franchise that was really necessary, and it seems odd that the most fantastic thing in a movie about AI, virtual reality and transhumanism is that one can get across Vancouver in under 29 minutes.

That’s just the films though. There’s more out there, more transmedia that fills in the storyline, including other video games and animated series and appearances and references in other pop culture. But we’re only digging into the films here on rewatching the movies. The three films done in three different eras with different kinds of technology have shifting takes on what it means to interact with computers despite similar scenes and story beats in all three films.

Difference and repetition, separated by decades. Of the three, I think I enjoyed Legacy the least as it felt of an age embodied within the dotcom and social media era, rather than looking forward with a fantastical view at stuff that does not exist, which both the original with virtual reality, Ares with digital materiality enabled via the permanence tech both did.

Legacy was inward looking, more about what happened within cyberspace, and it turns out that in 2025 that is less interesting than what happens in the real world. The films dealing more with the real world had a bigger impact. And the impact is huge. There’s a meme going around that the Tron movies were always boxed off as bombs, that Disney keeps coming back to it every 20 to 30 years to make fetch happen once again.

But the fact is that the meme just isn’t true. The series has always been a success, albeit a modest one compared to today’s billion dollar blockbusters. As we noted earlier, both the original Tron and Tron legacy profitably exceeded their production budgets and Tron Ares has made about 130 million after a few weeks of release on $180 million production.

So it’s a little bit low right now. These are pre-marketing figures, but it’s far from bombing though. Time will tell on Tron Ares final result, and the franchise has been ever present since its release, occupying space in arcades and on consoles since the 1980s and continue to being referred to in Geek Culture.

It’s inspired generations of computer programmers, graphics designers, and musicians interested in synthesizers, including Daft Punk who performed the soundtrack for the second movie. Will there be more Tron films in the future? Perhaps not. There might not be a fourth, but who knows what the future may hold.

The other question to ask is, does a movie still have the capacity to inspire us? If the monoculture is dead, fractured into thousands of shards, like a derezzing program in Legacy or Aries, then can a film take hold the same way, or does it even have to?

Tron was a modest success, but it found its audience. It became a classic within that niche. Perhaps that’s the real permanence code that we all seek to aspire to, to leave a lasting impact on the world.

Once again, thank you for joining us on the ImplausiPod. I’m your host, Dr. Implausible. You can reach me at Dr. implausible at implausipod.com and you can also find the show archives and transcripts of all our previous shows at implausipod.com as well. I’m responsible for all elements of the show, including research, writing, mixing, mastering, and music, and the show is licensed under a Creative Commons 4.0 ShareAlike license.

You may have also noted that there was no advertising during the program and there’s no cost associated with the show, but it does grow from word of mouth of the community. So if you enjoy the show, please share it with a friend or two and pass it along. There’s also a buy me a coffee link on each show at implausipod.com, which would go to any hosting costs associated with the show.

Over on the blog, we’ve started up a monthly newsletter. There will likely be some overlap with future podcast episodes and newsletter subscribers can get a hint of what’s to come ahead of time. So consider signing up and I’ll leave a link in the show notes. We hope to be back with you with another episode soon.

Until next time, take care and have fun.