(this was originally published as Implausipod Episode 37 on September 22nd, 2024)

https://www.implausipod.com/1935232/episodes/15791252-e0037-soylent-culture

What is Soylent Culture? Whether it is in the mass media, the new media, or the media consumed by the current crop of generative AI tools, it is culture that has been fed on itself. But of course, there’s more. Have a listen to find out how Soylent Culture is driving the potential for “Model Collapse” with our AI tools, and what that might mean.

In 1964, Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan published his work Understanding Media, The Extensions of Man. In it, he described how the content of any new medium is that of an older medium. This can help make it stronger and more intense. Quote, “The content of a movie is a novel, or a play, or an opera.

The effect of the movie form is not related to its programmed content. The content of writing or print is speech, but the reader is almost entirely unaware either of print or of speech.” End quote.

60 years later, in 2024, this is the promise of the generative AI tools that are spreading rapidly throughout society, and has been the end result of 30 years of new media, which has seen the digitalization of anything and everything that provides some form of content on the internet.

Our culture has been built on these successive waves of media, but what happens when there’s nothing left to feed the next wave? It begins to feed on itself, which is why we live now in an era of soylent culture.

Welcome to the Implausipod, an academic podcast about the intersection of art, technology, and popular culture. I’m your host, Dr. Implausible, and in this episode, we’re going to draw together some threads we’ve been collecting for over a year and weave them together into a tapestry that describes our current age, an era of soylent culture.

And way back in episode 8, when we introduced you to the idea of the audience commodity, where media companies real product isn’t the shiny stuff on screen, but rather the audiences that they can serve up to the advertisers, we noted how Reddit and Twitter were in a bit of a bind because other companies had come in and slurped up all the user generated content that was so fundamental to Web 2. 0 and fundamental to their business model as well, as they were still in that old model of courting the business of advertisers.

And all that UGC – the useless byproduct of having people chat online in a community that serve up to those advertisers – got tossed into the wood chipper, added a little bit of glue and paint, and then sold back to you as shiny new furniture, just like IKEA.

And this is what the AI companies are doing. We’ve been talking about this a little bit off and on, and since then, Reddit and Twitter have both gone all in on leveraging their own resources, and either creating their own AI models, like the Grok model, or at least licensing and selling it to other LLMs.

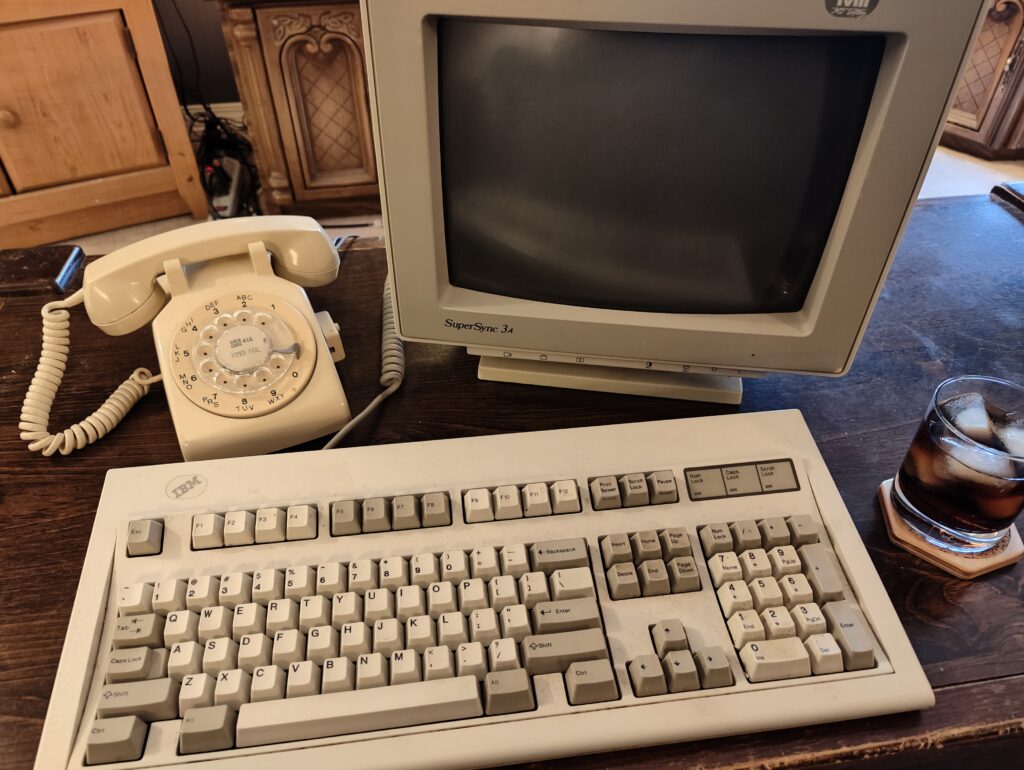

In episode 16, we looked a little bit more at that Web 2. 0 idea of spreadable media and how the atomization of culture actually took place. How the encouragement of that user generated content by the developers and platform owners is now the very material that’s feeding the AI models. And finally, our look at nostalgia over the past two episodes, starting with our look at the Dial-up Pastorale and that wistful approach to an earlier internet, one that never actually existed.

All of these point towards the existence of Soylent Culture. What I’m saying is is that it’s been a long time coming. The atomization of culture into its component parts, the reduction and eclipsed of soundbites to TikToks to Vines, the meme-ification of culture in general were all evidence of this happening.

This isn’t inherently a bad thing. We’re not ascribing some kind of value to this. We’re just describing how culture was reduced to its bare essentials as even smaller bits were carved off of the mass audience to draw the attention of even smaller and smaller niche audiences that could be catered to.

And a lot of this is because culture is inherently memetic. That’s memetic as in memes, not memetic as in mimesis, though the latter applies as well. But when we say that culture is memetic, I want to build on it more than just Dawkins’s original formulation of the idea of a meme to describe a unit of cultural transmission.

Because, honestly, the whole field of anthropology was sitting right over there when he came up with it. A memetic form of culture allows for the combination and recombination of various cultural components in the pursuit of novelty, and this can lead to innovation in the arts and the aesthetic dimension.

In the digital era, we’ve been presented with a new medium. Well, several perhaps, but the underlying logic of the digital media – the reduction of everything to bits, to ones and zeros that allow for the mass storage and fast transmission of everything anywhere, where the limiting factors are starting to boil down to fundamental laws of physics –

this commonality can be found across all the digital arts, whether it’s in images, audio, video, gaming. Anything that’s appearing on your computer or on your phone has this underlying logic to it. And when a new medium presents itself due to changing technology, the first forays into that new medium will often be adaptations or translations of work done in an earlier form.

As noted by Marshall McLuhan at the beginning of this episode, it can take a while for new media to come into its own. It’ll be grasped by the masses as popular entertainment and derided by the high arts, or at least those who are fans of it. Frederick Jameson, who we talked about a whole lot last episode on nostalgia noted, quote, “it was high culture in the fifties that was authorized as it still is to pass judgment on reality.

to say what real life is and what is mere appearance. And it is by leaving out, by ignoring, by passing over in silence and with the repugnance one may feel for the dreary stereotypes of television series that high art palpably issues its judgment.” End quote.

So, the new medium, or works that are done in the new medium, can often feel derivative as it copies stories of old, retelling them in a new way.

But over time, what we see happen again and again and again are that fresh stories start to be told by those familiar with the medium that have and can leverage the strengths and weaknesses of the medium, telling tales that reflect their own experiences, their own lives, and the lives of people living in the current age, not just reflections of earlier tales.

And eventually, the new medium finds acceptance, but it can take a little while.

So let me ask you, how long does it take for a new medium to be accepted as art? First they said radio wasn’t art, and then we got War of the Worlds. They said comic books weren’t art, and then we got Maus, and Watchmen, and Dark Knight Returns. They said rock and roll wasn’t art, and we got Dark Side of the Moon and Pet Sounds, Sgt.

Pepper’s and many, many others. They said films weren’t art, and we got Citizen Kane. They said video games weren’t art, and we got Final Fantasy VII and Myst and Breath of the Wild. They said TV wasn’t art, and we got Oz and Breaking Bad and Hannibal and The Wire. And now they’re telling us that AI generated art isn’t art, and I’m wondering how long it will take until they admit that they were wrong here, too.

Because even though it’s early days, I’ve seen and heard some AI generated art pieces that would absolutely count as art. There are pieces that produce an emotional effect, they evoke a response, whether it’s whimsy or wonder or sublime awe, and for all of these reasons, I think the AI generated art that I’ve seen or experienced counts.

And the point at which creators in a new medium produce something that counts as art often happens relatively early in the life cycle of that new media. In all of the examples I gave, things like War of the Worlds, Citizen Kane, Final Fantasy VII, these weren’t the first titles produced in that medium, but they did come about relatively early, once creators became accustomed to the cultural form.

As newer creators began working with the media, they can take it further, but there’s a risk. Creators that have grown up with the media may become too familiar with the source material, drawing on the representations from within itself. And we can all think of examples of this, where writers on police procedurals or action movies have grown up watching police procedurals and action movies and they simply endlessly repeat the tropes that are foundational to the genre.

The works become pastiches, parodies of themselves, often unintentionally, and they’re unable to escape from the weight of the tropes that they carry. This is especially evident in long running shows and franchises. Think of later seasons of The Simpsons, if you’ve actually watched recent seasons of The Simpsons, compared to the earlier ones.

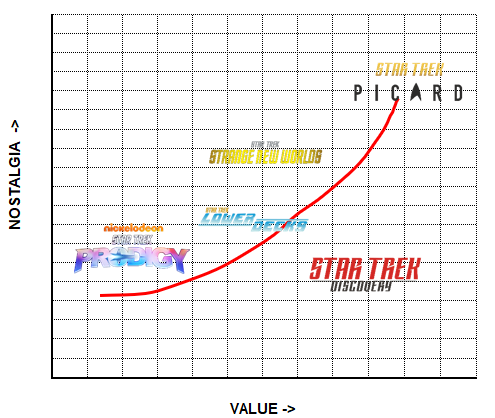

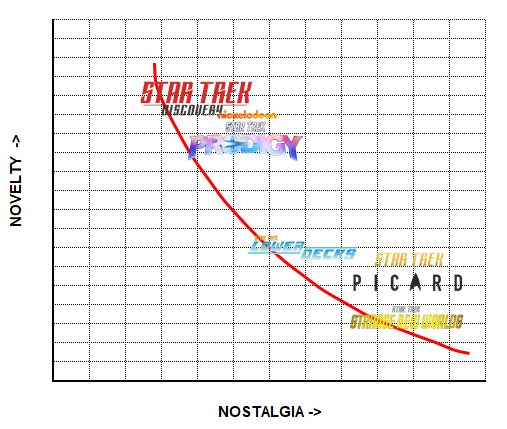

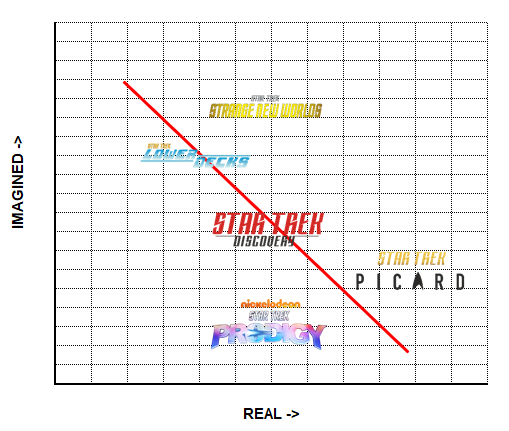

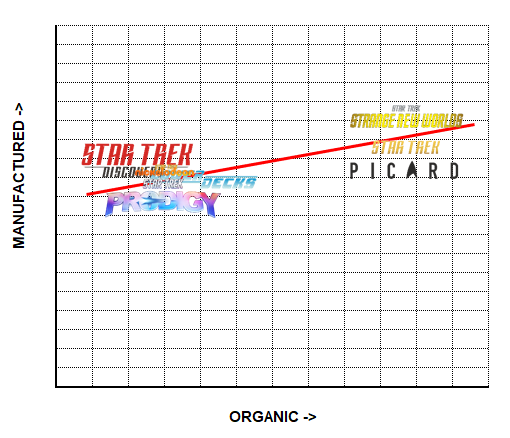

Or recent seasons of Saturday Night Live, with the endlessly recycled bits, because we really needed another game show knock off, or a cringy community access parody. We can see it in later seasons of Doctor Who, and Star Trek, and Star Wars, and Pro Wrestling as well, and the granddaddy of them all, the soap opera.

This is what happens with normal culture when it is trained on itself. You get Soylent Culture.

Soylent Culture is this, the self referential culture that is fed on itself, an ouroboros of references that always point at something else. It is culture comprised of rapid fire clips coming at the audience faster than a Dennis Miller era Saturday Night Live weekend update. Or the speed of a Weird Al Yankovic polka medley.

It is 30 years of Simpsons Halloween episodes referring to the first 10 years of Simpsons Halloween episodes. It is the hyper referential titles like The Family Guy and Deadpool, whether in print or film, throwing references at the audience rapid fire with rhyme and reason but so little of it, that works like Ready Player One start to seem like the inevitable result of the form.

And I’m not suggesting that the above works aren’t creative. They’re high examples of this cultural form; of soylent culture. But the endless demand for fresh material in an era of consumption culture means that the hyper-referentiality will soon exhaust itself and turn inward. This is where the nostalgia that we’ve been discussing for the previous couple episodes comes into play.

It’s a resource for mining, providing variations of previous works to spark a glimmer in the audience’s eyes of, hey, I recognize that. But even though these works are creative, they’re limited, they’re bound to previous, more popular titles, referring to art that was more widely accessible, more widely known.

They’re derivative works and they can’t come up with anything new, perhaps.

And I say perhaps because there’s more out there than we can know. There’s more art that’s been created that we can possibly experience in a lifetime. There’s more stuff posted to YouTube in a minute than you’ll ever see in your 80 years on the planet.

And the rate at which that is happening is increasing. So, for anybody watching these hyper referential titles, if their first exposure to Faulkner is through Family Guy, or to Diogenes is through Deadpool, then so be it. Maybe their curiosity will inspire them to track that down, to check out the originals, to get a broader sense of the culture that they’re immersed in.

If they don’t get the joke and look around and wonder why the rest of the audience is laughing at this and say, you know, maybe it’s a me thing. Maybe I need to learn more. And that’s all right. It can lead to an act of discovery; of somebody looking at other titles and curating them, bringing them together and developing their own sense of style and working on that to create an aesthetic.

And that’s ultimately what it comes down to. Is art an act of learning and discovery and curation? Or is it an act of invention and generation and creation, or these all components of it? If an artist’s aesthetic is reliant on what they’ve experienced, well, then, as I’ve said, we’re finite, tiny creatures.

How many books or TV shows can you watch in a lifetime to incorporate into your experience? And if you repeatedly watch something, the same thing, are you limiting yourself from exposure to something new? And this is where the generative art tools come back into play. The AI tools that have been facilitated by the digitalization of everything during web 1. 0 and the subsequent slurping up of everything into feeding the models.

Because the AI tools expand the realm of what we have access to. They can draw from every movie ever made, or at least digitalized. Not just the two dozen titles that the video store clerked happened to watch on repeat while they were working on their script, before finally following through and getting it made.

In theory, the AI tools can aid the creativity of those engaging with it, and in practice we’re starting to see that as well. It comes back to that question of whether art is generative or whether it’s an act of discovery and curation. But there’s a catch. Like we said, Soylent cultures existed long before the AI art tools arrived on the scene.

The derivative stories of soap operas and police procedurals and comic books and pulp sci-fi. But it has become increasingly obvious that the AI tools facilitate Soylent culture, drive it forward, and feed off of it even more. The A. I. tools are voracious, continually wanting more, needing fresh new stuff in order to increase the fidelity of the model.

That hallowed heart that drives the beast that continually hungers. But you see, the model is weak. It is Vulnerable like the phylactery of a lich hidden away somewhere deep.

The one thing the model can’t take too much of is itself: model collapse is the very real risk of a GPT being trained on text generated by a large language model identified by Shumailov, et al, and “ubiquitous among all learned generative models” end quote. Model collapse is a risk that creators of AI tools face in further developing those tools.

Quoting again from Shumailov: “model collapse is a degenerative process affecting generations of learned generative models in which the data they generate end up polluting the training set. of the next generation. Being trained on polluted data, they then misperceive reality.” End quote. This model collapse can result in the models ‘forgetting’ or ‘hallucinating’.

Two terms drawn not just from psychology, but from our own long history of engaging with and thinking about our own minds and the minds of others. And we’re exacting them here to apply to our AI tools, which – I want to be clear – aren’t thinking, but are the results of generative processes of taking lots of things and putting them together in new ways, which is honestly what we do for art too.

But this ‘forgetting’ can be toxic to the models. It’s like a cybernetic prion disease, like the cattle that developed BSE by being fed feed that contained parts of other ground up cows that were sick with the disease. The burgeoning electronic minds of our AI tools cannot digest other generated content.

And in an era of Soylent Culture, where there’s a risk of model collapse, where these incredibly expensive AI tools that require mothballed nuclear reactors to be brought online to provide enough power to service them, that thirst for fresh water like a marathon runner in the desert, In this era, then the human generated content of the earlier pre AI web becomes a much more valuable resource, the digital equivalent of the low background steel that was sought after for the creation of precision instruments following the era of atmospheric nuclear testing, where all the above ground and newly mined ore was too irradiated for use in precision instruments.

And it should be noted that we’re no longer living in that era because we stopped doing atmospheric nuclear testing. And for some, the takeaway for that may be that to stop an era of Soylent culture, we may need to stop using these AI tools completely. But I think that would be the wrong takeaway because the Soylent culture existed long before the AI tools existed, long before new media, as shown by the soap operas and the like.

And it’s something that’s more tied to mass culture in general, though. New media and the AI tools can make Soylent Culture much, much worse, let me be clear. Despite this, despite the speed with which all this is happening, the research on model collapse is still in its early days. The long term ramifications of model collapse and its consequences will only be learned through time.

In the meantime, we can discuss some possible solutions to dealing with Soylent Culture. Both AI generated and otherwise. If Soylent Culture is art that’s fed on itself, then the most effective way to combat it would be to find new stuff. To find new things to tell stories about. To create new art about.

Historically, how has this happened with traditional art? Well, we’ve hinted at a few ways throughout this episode, even though, as we noted, in an era of mass culture, even traditional arts are not immune from becoming soylent culture as well. One of the ways we get those new artistic ideas is through mimesis, the observation of the world around us, and imitating that, putting it into artistic forms.

Another way we get new art is through soft innovation when technologies enhance or change the way that we can produce media and art, or where art inspires the development of new technology as they feed back and forth between each other, trading ideas. And as we’ve seen throughout this episode and throughout the podcast in general, new media and new modes of production can encourage new stories to be told as artists are dealing with their surroundings and whatever the current zeitgeist is and putting that into production with whatever media that they have available.

As our world and society and culture changes, we’re going to reflect upon our current condition and tell tales about that to share with those around us. And as we noted much. Earlier in this particular episode, that familiarity with a form, a technical form, allows those who are using it to innovate within that form, creating new, more complex, better produced and higher fidelity works in whatever medium they happen to be choosing to work in.

And ultimately that comes down to choice. By the artists and the audience and the associated industries that allow the audience to experience those works, whether they are audio, visual, tactile, experiential, like games, any version of art that we might come in contact with. The generation and invention in the process is important to be sure, but the curation and discovery is no less important within this process.

And this is where humans with an a sense for aesthetic and style will still be able to tell. How would an AI tool discover or create? How could it test something that’s in the loop? The generative AI tools can’t tell. They have no sense. They can provide output, but no aura, no discernment. Could an AI run a script that does A-B testing on an audience for each new generated piece of art to see how they react, and the most popular one gets put forward?

I guess so, it’s not outside the realm of possibility, but that isn’t really something that they’re able to do on their own, or at least I hope not.

Would programming in some variance and randomness in the AI tools allow for them to avoid the model collapse that comes with ingesting soylent culture in much the same way that we saw with the reveries for the hosts in the Westworld TV series?

Well, the research by Shumailov et al that we mentioned earlier suggests that that’s possibly not the case. I mean, it might help with the variation, perhaps, but that doesn’t help with the selection mechanisms, the discernment.

AI is a blind watch, trying to become a watchmaker, making new watches. The question might be, what would an AI even want with a watch anyways?

Thank you for joining us on the Implausipod. I’m your host Dr. Implausible. We’ll explore more on the current state of AI art tools and their role as assistive technologies in our next episode. called AI Refractions. But before we get there, we need to return to our last episode, episode 36, and offer a postscript on that one.

Even though it’s been only a week, as of the recording of this episode, September 22nd, 2024, we regret to inform you of the passing of Professor Frederick Jameson, who was the subject of episode 36. As we noted in that episode, he was a giant in the field of literary criticism and philosophy, and a long time professor at Duke University.

Our condolences go out to his family and friends. Rest in peace. If you’d like to contact the show, you can reach me at drimplausible at implausipod. com, and you can also find the show archives and transcripts of all our previous shows at implausipod. com as well. I’m responsible for all elements of the show, including research, writing, mixing, mastering, and music, and the show is licensed under a Creative Commons 4. 0 share alike license.

You may have noticed at the beginning of the show that we described the show as an academic podcast, and you should be able to find us on the Academic Podcast Network when that gets updated. You may have also noted that there was no advertising during the program, and there is no cost associated with the show, but it does grow from word of mouth of the community, so if you enjoy the show, please share it with a friend or two.

and pass it along. There’s also a buy me a coffee link on each show at implausipod. com which will go to any hosting costs associated with the show. Over on the blog, we’ve started up a monthly newsletter. There will likely be some overlap with future podcast episodes, and newsletter subscribers can get a hint of what’s to come ahead of time, so consider signing up and I’ll leave a link in the show notes.

Until then, take care and have fun.

Bibliography

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. The New American Library.

Shumailov, I., Shumaylov, Z., Zhao, Y., Gal, Y., Papernot, N., & Anderson, R. (2024). The Curse of Recursion: Training on Generated Data Makes Models Forget (No. arXiv:2305.17493). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.17493

Shumailov, I., Shumaylov, Z., Zhao, Y., Papernot, N., Anderson, R., & Gal, Y. (2024). AI models collapse when trained on recursively generated data. Nature, 631(8022), 755–759. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07566-y

Snoswell, A. J. (2024, August 19). What is ‘model collapse’? An expert explains the rumours about an impending AI doom. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/what-is-model-collapse-an-expert-explains-the-rumours-about-an-impending-ai-doom-236415