In the most recent Newsletter (Issue 11), I mentioned how there was a lot of movies and media that I experienced that would have been a good fit for the “Multi-Melting” section. Or individual posts. But as time slipped out of the moment, it felt a little weird to wedge them all in. So let’s recap the summer of 2025 here:

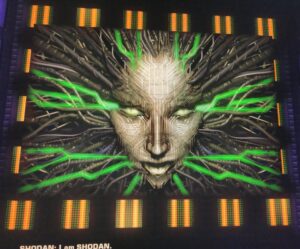

System Shock 2 (2025 Remaster)

In the late 1990s video gaming was undergoing a real paradigm shift, and this was most apparent in the FPS genre. The trifecta of post-Doom FPSs that moved the genre forward includes Half Life (1998), Deus Ex (2000), and System Shock 2 (2000). They brought innovations to the genre that are still with us today: branching missions, novel environments, game story embedded in the environment as you play through. Weapon upgrades, skill upgrades, and multiple paths to success.

I played a lot of these three back when they came out, and I was happy to finally see SS2 make the light of day in the remastered version. It plays smoothly, and the high res textures are nice, though later levels of the ship feel almost barren by today’s standards, so they didn’t add a lot to the maps for the new version, save for the textures. Feels a little empty, somehow, and not just in the “desolate spaceship” way.

While both Half-Life and Deus Ex had a few sequels, SS2 didn’t, though it was (spiritually) followed by the Bioshock series which most modern gamers may be more familiar with. They haven’t had the chance to experience the horror of the decrepit spaceship in the original release. 25 years later there’s still something to hearing that synthesized voice call you “insect” that reverberates and shakes you to your core. Still a great game, worth tracking down.

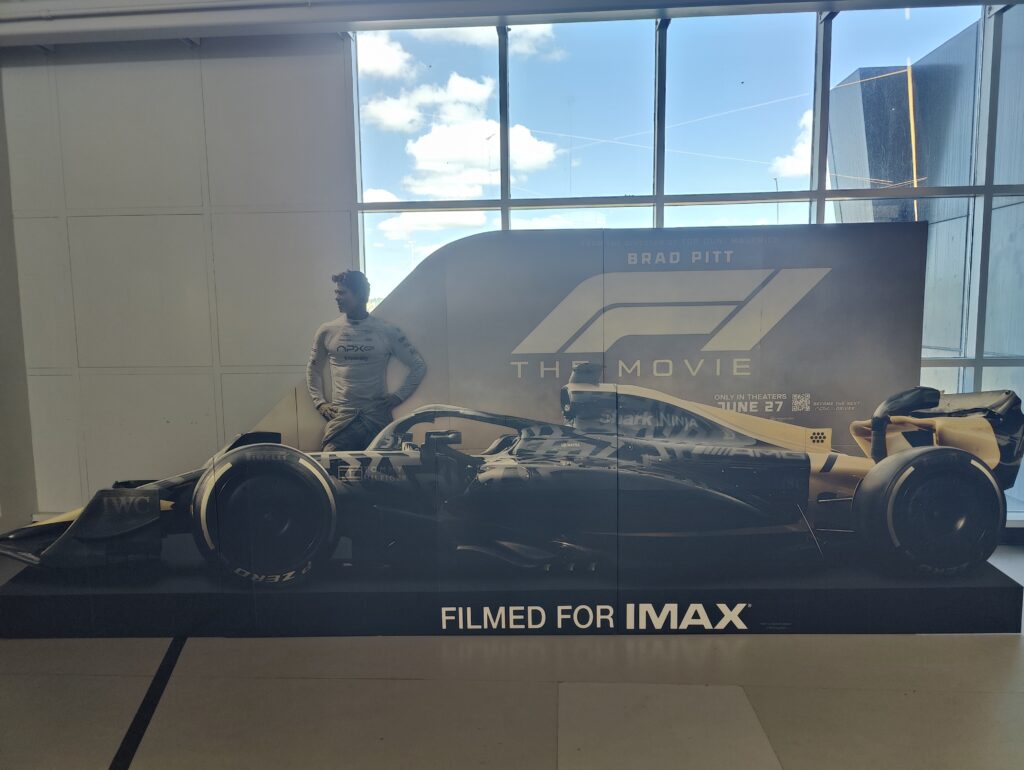

F1 (2025)

Saw it the weekend after it came out. All the action and cinematography you’ve come to expect from a Bruckheimer film, along with all the acting and plot you’ve come to expect from a Bruckheimer film. Saw it on IMAX, which is the recommended viewing scale (it really does look awesome), but this two-hour long ode to product placement was a little slow at times. This was mostly due to staying overlong on certain races, where the minutiae of the lap-by-lap progression didn’t impact the overall result that much*. Let’s score it a 6.

* Spoiler: much like Brad Pitt’s character arc. Him ending up where he started, looking to take a race in Baja, essentially meant that his impact was minimal, and the entire F1 “season” could have been a daydream or in his head while he recovered from injury.

Superman (2025)

Hey, turns out that bright summer movies are fun! There was a lot I enjoyed in this latest Superman movie. Most of that is due to it’s assumption of the intelligence of the audience, that we could figure stuff our as we went along, and that we didn’t need a deep origin story at the outset, just the 4 lines of text in a scroll and cut to the action. (Yes, there is some info about the origin, but it’s interleaved throughout the story, and again, the movie trusts us to figure it out).

There are some probs, mostly in the action sequences feeling weightless in that way peculiar to superhero movies and the Fast and Furious franchise. My eyes tend to glaze over during these fights. A few other misses in there too, but otherwise – fun and enjoyable. I’d give it a solid 7

Great Outdoor Comedy Festival Thoughts

A quick little road trip to check out the Great Outdoor Comedy Festival (GOCF), and this ended up being a lot of fun. Held at Kinsmen Park in Edmonton, Alberta, this massive green space provided a huge audience for the performers.

But it took a little while to get going. For the pre-show we had a musician doing the Ed Sheeran acoustic guitar with a looper schtick for a few songs. Then a video package of the history of the GOCF, and an introduction by the MC, who is apparently TikTok famous for something or other.

We finally got to the main event around 9pm or so. First up was Melissa Villasenor, late of SNL where she was for 6 years. She’s supremely talented, but comes across a bit nervous, and not as a stand up, or at least not with the reps behind her and level of polish the others had.

Pete Holmes was next, with a decent amount of energy which he flipped to build a good rapport with the crowd. He seemed to be enjoying the venue and the giant stage with an outdoor crowd. This can be said for Nick Kroll too: both of them commented on the nature of the event, the chilly temp even in midsummer, and the sunlight staying out late, til 10 pm. Kroll surprised me a bit, as I haven’t seen much of his stand-up work but he was engaging and funny, firing off the jokes rapid-fire.

Anthony Jeselnik was the headliner, and despite seeing some of his earlier stuff, I feel like he was the weaker of the major acts – putting him behind Holmes and Kroll, as least on this night. I know he just released a special last year, so he’s in the middle of working on new material, but it just wasn’t clicking. The set was disjointed, and there wasn’t a lot of flow between jokes. Maybe this is him shortening the set for the festival format; hard to say. Definitely felt off.

Overall though, a good experience. Will I go again? Sure. Will I travel over 300 km for it? Less likely. Not enough that’ll pre-buy a ticket for next year without knowing the full lineup.

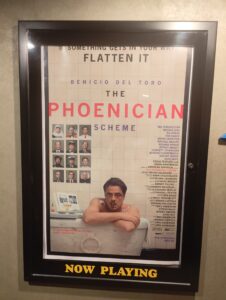

The Phoenician Scheme (2025)

A few years ago I caught The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) at the cheap theaters solely on the basis of seeing the trailer in front of a Marvel movie (probably Cap 2, though the Marvel releases have blurred with age). And I absolutely adored it.

This was not that movie, though so much of the DNA was there. You can trace the lineage: the quirky characters, the rapid dialogue, the innovative sets, the intentional use of colour, all these things that show the intentionality behind all the choices, and still have it come away flat. I’m not sure what the missing spark was, perhaps Del Toro’s traditional mumbling line delivery, or the lack of electricity between the characters, or not really being able to identify with the lives of rich criminals who flaunt the rules in the current era (though saying that out loud, I think we hit on the answer). But overall, I felt it was overlong and boring, despite recognizing the level of artistry and craft that went into it. 4/10, not recommended.

Monument Valley (2014/2022)

Grabbed this as an Epic Games freebie, a puzzle game that had been released a decade ago on mobile that was recently available on PC. I really liked this, taking my time to work through a level or two an evening, and really exploring the game. I’m not sure if this is the best example of “non-Euclidean geometry” of classic Cthulhu lore, but if anyone ever needed an explanation, I’d point them this way. Recommended.

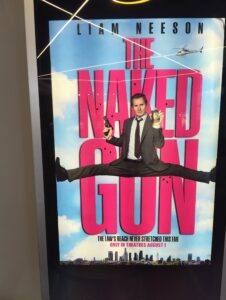

Naked Gun (2025) Thoughts

Sometimes, you need a break from the inherent silliness of the superhero movies, and so the inherent silliness of a Naked Gun movie serves as a suitable distraction. Wasn’t sure about seeing this initially, but good word of mouth on the opening weekend made it worth checking out.

This is one of those movies that’s enjoyable in the moment but flits away from your memory as soon as you leave the theatre. It’s odd, in that it is both move and less over the top the the original Leslie Nielsen flicks, in that it tries hard but blazes well past the point of absurdity, and also lacks the volume of gags that were in the originals as well.

But we shouldn’t criticize the films for not being their predecessors. It’s a light, fun, absurb romp, a quick 90 minute gag fest, and both Liam Neeson and Pamela Anderson are engaging in their roles. I had fun in the moment, and the movie made me smile. 6 out of 10.