(this was originally published as Implausipod Episode 38 on October 5th, 2024)

https://www.implausipod.com/1935232/episodes/15804659-e0038-ai-refractions

Looking back in the year since the publication of our AI Reflections episode, we take a look at the state of the AI discourse at large, where recent controversies including those surrounding NaNoWriMo and whether AI counts as art, or can assist with science, bring the challenges of studying the new medium to the forefront.

In 2024, AI is still all the rage, but some are starting to question what it’s good for. There’s even a few that will claim that there’s no good use for AI whatsoever, though this denialist argument takes it a little bit too far. We took a look at some of the positive uses of AI a little over a year ago in an episode titled AI Reflections.

But it’s time to check out the current state of the art, take another look into the mirror and see if it’s cracked. So welcome to AI Refractions, this episode of ImplausiPod.

Welcome to The ImplausiPod, an academic podcast about the intersection of art, technology, and popular culture. I’m your host, Dr. Implausible. And in this episode, we’ve got a lot to catch up on with respect to AI. So we’re going to look at some of the positive uses that have come up and how AI relates to creativity and statements from NaNoWriMo caused a bit of controversy.

And how that leads into AI’s use in science. But it’s not all sunny over in AI land. We’ve looked at some of the concerns before with things like Echange, and we’ll look at some of the current critiques as well. And then look at the value proposition for AI, and how recent shakeups with open AI in September of 2024 might relate to that.

So we’ve got a lot to cover here on our near one year anniversary of that AI Reflections episode, so let’s get into it. We’ve mentioned AI a few other times since that episode aired in August of 2023. It came up in episode 28, our discussion on black boxes and the role of AI handhelds, as well as episode 31 when we looked at AI as a general purpose technology.

And it also came up a little bit in our discussion about the arts, things like Echanger and the Sphere, and how AI might be used to assist in higher fidelity productions. So it’s been an underlying theme about a lot of our episodes. And I think that’s just the nature of where we sit with relation to culture and technology.

When you spend your academic career studying the emergence of high technology and how it’s created and developed, when a new one comes on the scene, or at least becomes widely commercially available, you’re going to spend a lot of time talking about it. And we’ve been obviously talking about it for a while.

So if you’ve been with us for a while, first off, you’re Thank you, and this may be familiar to you, and if you just started listening recently, welcome, and feel free to check out those episodes that we mentioned earlier. I’ll put links to the specific ones in the text. And looking back at episode 12, we started by laying down a definition of technology.

We looked at how it functioned as an extension of man, to borrow from Marshall McLuhan, but the working definition of technology that I use, the one that I published in my PhD, is that “Technology is the material embodiment of an artifact and its associated systems, materials, and practices employed to achieve human ends.”

And this definition of technology covers everything from the sharp stick and sharp stick- related technologies like spears, pencils, and chopsticks, to our more advanced tech like satellites and AI and VR and robots and stuff. When you really think about it, it’s a very expansive definition, but that helps us in its utility in allowing us to recognize and identify things.

And by being able to cover everything from sharp sticks to satellites, from language to pharmaceuticals to games, it really covers the gamut of things that humans use technology for, and contributes to our view of technology as an emancipatory view. That technology is ultimately assistive and can aid us in issues that we’re struggling with.

We recognize that there’s other views and perspectives, but this is where we fall down on the spectrum. Returning back to episode 12, we showed how this emancipatory stance contributes to an empathetic view of technology, where we can step outside of our own frame of reference and think about how technology can be used by somebody who isn’t us.

Whether it’s a loved one, somebody close to us, or even a member of our community or collective, or you. More widely ranging, somebody that we’ll never come into contact with. How persons with different abilities and backgrounds will find different uses for the technology. Like the famous quote goes, “the street finds its own uses for things.”

Maybe we’ll return back to that in a sec. We finished off episode 12 looking at some of the positive uses of AI at that time that had been published just within a few weeks of us recording that episode. People were recounting how they were finding it as an aid or an enhancement to their creativity, and news stories were detailing how the predictive text abilities as well as generative AI facial animations could help stroke victims, as well as persons with ALS being able to converse at a regular tempo.

So by and large it could function as an assistive technology, and in recent weeks we have started trying to Catalogue all those stories. Back in July over on the blog we created the Positive AI Archive, a place where I could put those links to all the stories that I come across. Me being me, I forgot to update it since, but we’ll get those links up there and you should be able to follow along.

We’ll put the link to the archive in the show notes regardless. And, in the interest of positivity, that’s kinda where I wanted to start the show.

The street finds its own uses for things. It’s a great quote from Burning Chrome, a collection of short stories by William Gibson. It’s the one that held Johnny Mnemonic, which led to the film with Keanu Reeves, and then subsequently The Matrix and Cyberpunk 2077 and all those other derivative works. The street finds its own uses for things is a nuanced phrase and nuance can be required when we’re talking about things, especially online when everything gets reduced to a soundbite or a five second dance clip.

The street finds its own uses for things is a bit of a mantra and it’s one that I use when I’m studying the impacts of technology and what “the street finds its own uses for things” means is that the end users may put a given technology to tasks that its creators and developers never saw. Or even intended.

And what I’ve been preaching here, what I mentioned earlier, is the empathetic view of technology. And we look at who benefits from using that technology, and what we find with the AI tools is that there are benefits. The street is finding its own uses for AI. In August of 2024, a number of news reports talked about Casey Harrell, a 46 year old father suffering from ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, who was able to communicate with his daughter using a combination of brain implants and AI assisted text and speech generation.

Some of the work on these assistive technologies was done with grant money, and there’s more information about the details behind that work, and I’ll link to that article here. There’s multiple technologies that go into this, and we’re finding that with the AI tools, there’s very real benefits for persons with disabilities and their families.

Another thing we can do when we’re evaluating a technology is see where it’s actually used, where the street is located. And when it comes to assistive AI tools like ChatGPT, The street might not be where you think it is. In a recent survey published by Boston Consulting Group in August of 2024, they showed where the usage of ChatGPT was the highest.

It’s hard to visually describe a chart, obviously, but at the top of the scale, we saw countries like India, Morocco, Argentina, Brazil, Indonesia. English speaking countries like the US, Australia, and the UK were much further down on the chart. The country where ChatGPT is finding its most adoption are countries where English is not the primary language.

They’re in the global south, countries with large populations that have also had to deal with centuries of exploitation. And that isn’t to say that the citizens of these countries don’t have concerns, they do, but they’re using it as an assistive technology. They’re using it for translation, to remove barriers and to help reduce friction, and to customize their own experience. And these are just a fraction of the stories that are out there.

So there are positive use cases for AI, which may seem to directly contradict various denialist arguments that are trying to gaslight you into believing that there is no good use for AI. This is obviously false.

If the positive view, the use on the street, is being found by persons with disabilities, it follows that the denialist view is ableist. If the positive view, that use on the street, is being found by persons of color, non English speakers, persons in the global south, then the denialist view will carry all those elements of oppression, racism, and colonialism with it.

If the use on the street is by Those who find their creativity unlocked by the new tools and they’re finally able to express themselves where previously they may have struggled with a medium or been gatekept from having an arts education or poetry or English or what have you, only to now find themselves told that this isn’t art or this doesn’t count despite all evidence to the contrary, then there’s massive elements of class and bias that go into that as well.

So let’s be clear. An empathetic view of technology recognizes that there are positive use cases for AI. These are being found on the street by persons with disabilities, persons of the global south, non english speakers, and persons across the class spectrum. To deny this is to deny objective reality.

It’s to deny all these groups their actual uses of the technology. Are there problems? Yes, absolutely. Are there bad actors that may use the technology for nefarious means? Of course, this happens on a regular basis, and we’ll put a pin in that and return to that in a few moments, but to deny that there are no good uses is to deny the experience of all these groups that are finding uses for it, and we’re starting to see that when this denialism is pointed out, it’s causing a great degree of controversy.

In a statement made early in September of 2024, NaNoWriMo, the non profit organization behind National Novel Writing Month, it was acceptable to use AI as an assistive technology when writers were working on their pieces for NaNoWriMo, because this supports their mission, which is to quote, “provide the structure, community, and encouragement to help people use their voices, achieve creative goals, and build new worlds, on and off the page.” End quote.

But what drew the opprobrium of the online community is that they noted that some of the objections to the use of AI tools are classist and ableist. And, as we noted, they weren’t wrong. For all the reasons we just explained and more. But, due to the online uproar, they’ve walked that back somewhat.

I’ll link to the updated statement in the show. The thing is, if you believe that using AI for something like NaNoWriMo is against the spirit of things, that’s your decision. They’ve clearly stated that they feel that assistive technologies can help for people pursuing their dreams. And if you have concerns that they’re going to take stuff that’s put into the official app and sell it off to an LLM or AI company, well, that’s a discussion you need to have with NaNoWriMo, the nonprofit.

You’re still not held off from doing something like NaNoWriMo using notepad or obsidian or however else you take your notes, but that’s your call. I for one was glad to see that NaNoWriMo called it out. One of the things that I found both in my personal life, as well as in my research, when I was working on the PhD and looking at Tikkun Olam Makers is that it can be incredibly difficult and expensive for persons with disabilities to find a tool that can meet their needs, if it exists at all. So if you’re wondering where I come down on this, I’m on the side of the persons in need. We’re on the side of the streets. You might say we’re streets ahead.

Of course, one of the uses that the street finds for things has always been art. Or at least work that eventually gets recognized as art. It took a long time for the world to recognize that the graffiti of a street artist might count, but in 2024, if one was to argue that Banksy wasn’t an artist, you’d get some funny looks.

There are several threads of debates surrounding AI art, generative art, including the role of creativity, the provenance of the materials, the ethics of using the tools, but the primary question is what counts? What counts as art and who decides that it counts? That’s the point that we’re really raising with that question, and obviously it ties back to what we were talking about last episode when it comes to Soylent Culture, and before that when we were talking about the recently deceased Frederick Jameson as well.

In his work Nostalgia for the Present from 1989, Jameson mentioned this with respect to television. He said, Quote, “At the time, however, it was high culture in the 1950s who was authorized, as it still is, to pass judgment on reality, to say what real life is and what is mere appearance. And it is by leaving out, by ignoring, by passing over in silence and with the repugnance one may feel for the dreary stereotypes of television series, that high art palpably issues its judgments.” end quote.

Now, High Art in Bunny Quotes isn’t issuing anything, obviously, Jameson’s reifying the term, but what Jameson is getting at is that there’s stakes for those involved about what does and does not count. And we talked about this last episode, where it took a long time for various forms of new media to finally be accepted as art on its own terms.

For some, it takes longer than others. I mean, Jameson was talking about television in the 1980s, for something that had already existed for decades at that point. And even then, it wasn’t until the 90s and 2000s, to the eras of Oz and The Sopranos and Breaking Bad and Mad Men and the quote unquote “golden age of television” that it really began to be recognized and accepted as art on its own terms.

Television was seen as disposable ephemera for decades upon decades. There’s a lot of work that goes on on behalf of high art by those invested in it to valorize it and ensure that it maintains its position. This is why we see one of the critiques about A. I. art being that it lacks creativity, that it is simply theft.

As if the provenance of the materials that get used in the creation of art suddenly matter on whether it counts or not. It would be as if the conditions in the mines of Afghanistan for the lapis lazuli that was crushed to make the ultramarine used by Vermeer had a material impact on whether his painting counted as art. Or if the gold and jewels that went into the creation of the Fabergé eggs and were subsequently gifted to the Russian royal family mattered as to whether those count. It’s a nonsense argument. It makes no sense. And it’s completely orthogonal to the question of whether these works count as art.

And similarly, where people say that good artists borrow, great artists steal, well, we’ll concede that Picasso might have known a thing or two about art, but Where exactly are they stealing it from? The artists aren’t exactly tippy toeing into the art gallery and yoinking it off the walls now, are they?

No, they’re stealing it from memory, from their experience of that thing, and the memory is the key. Here, I’ll share a quote. “Art consists in bringing the memory of things past to the surface. But the author is not a Paessiest. He is a link to history, to memory, which is linked to the common dream.” This is of course a quote by Saul Bellow, talking about his field, literature, and while I know nowadays not as many people are as familiar with his work, if you’re at a computer while you’re listening to this, it might be worth to just look him up.

Are we back? Awesome. Alright, so what the Nobel Prize Laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner Saul Bellow was getting at is that art is an act of memory, and we’ve been going in depth into memory in the last three episodes. And the artist can only work with what they have access to, what they’ve experienced during the course of their lifetime.

The more they’ve experienced, the more they can draw on and put into their art. And this is where the AI art tools come in as an assistive technology, because they would have access to much, much more than a human being can experience, right? Possibly anything that has been stored and put into the database and the creator accessing that tool will have access to everything, all the memory scanned and stored within it as well.

And so then the act of art becomes one of curation of deciding what to put forth. AI art is a digital art form, or at least everything that’s been produced to date. So how does that differ? Right? Well, let me give you an example. If I reach over to my paint shelf and grab an ultramarine paint, right, a cheap Daler Rowney acrylic ink, it’s right there with all the other colors that might be available to me on my paint shelf.

But, back in the day, if we were looking for a specific blue paint, an ultramarine, it would be made with lapis lazuli, like the stuff that Vermeer was looking for. It would be incredibly expensive, and so the artist would be limited in their selection to the paints that they had available to them, or be limited in the amount that they could actually paint within a given year.

And sometimes the cost would be exorbitant. For some paints, it still actually is, but a digital artist working on an iPad or a Wacom tablet or whatever would have access to a nigh unlimited range of colors. And so the only choice and selection for that artist is by deciding what’s right for the piece that they’re doing.

The digital artist is not working with a limited palette of, you know, a dozen paints or whatever they happen to have on hand. It’s a different kind of thing entirely. The digital artist has a much wider range of things to choose from, but it still requires skill. You know, conceptualization, composition, planning, visualization.

There’s still artistry involved. It’s no less art, but it’s a different kind of art. But one that already exists today and one that’s already existed for hundreds of years. And because of a banger that just got dropped in the last couple of weeks, it might be eligible for a Grammy next year. It’s an allographic art.

And if you’re going to try and tell me that Mozart isn’t an artist, I’m going to have a hard time believing you.

Allographic art is a type of art that was originally introduced by Nelson Goodman back in the 60s and 70s. Goodman is kind of like Gordon Freeman, except, you know, not a particle physicist. He was a mathematician and aesthetician, or sorry, philosopher interested in aesthetics, not esthetician as we normally call them now, which has a bit of a different meaning and is a reminder that I probably need to book a pedicure.

Nelson was interested in the question of what’s the difference between a painting and a symphony, and it rests on the idea of like uniqueness versus forgery. A painting, especially an oil painting, can be forged, but it relies on the strokes and the process and the materials that went into it, so you need to basically replicate the entire thing while doing it in order to make an accurate forgery, much like Pierre Menard trying to reproduce Cervantes ‘Quixote’ in the Jorge Luis Borges short story.

Whereas a symphony, or any song really, that is performed based off of a score, a notational system, is simply going to be a reproduction of that thing. And this is basically what Walter Benjamin was getting at when he was talking about art in the age of mechanical reproduction, too, right? So, a work that’s based off of a notational system can still count as a work of art.

Like, no one’s going to argue that a symphony doesn’t count as art, or that Mozart wasn’t an artist. And we can extend that to other forms of art that use a notational system as well. Like, I don’t know, architecture. Frank Lloyd Wright didn’t personally build Falling Water or the Guggenheim, but he created the plans for it, right?

And those were enacted. He did. We can say that, yeah, there’s artistic value there. So these things, composition, architecture, et cetera, are allographic arts, as opposed to autographic arts, things like painting or sculpture, or in some instances, the performance of an allographic work. If I go to see an orchestra playing a symphony, a work based off of a score, I’m not saying that I’m not engaged with art.

And this brings us back to the AI Art question, because one of the arguments you often see against it is that it’s just, you know, typing in some prompts to a computer and then poof, getting some results back. At a very high level, this is an approximation of what’s going on, but it kind of misses some of the finer points, right?

When we look at notational systems, we could have a very, you know, simple set of notes that are there, or we could have a very complex one. We could be looking at the score for Chopsticks or Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, or a long lost piece by Mozart called Serenade in C Major that he wrote when he was a teenager and has finally come to light.

This is an allographic art, and the fact that it can be produced and played 250 years later kind of proves the point. But that difference between simplicity and complexity is part of the key. When we look at the prompts that are input into a computer, we rarely see something with the complexity of say a Mozart.

As we increase the complexity of what we’re putting into one of the generative AI tools, we increase the complexity of what we get back as well. And this is not to suggest that the current AI artists are operating at the level of Mozart either. Some of the earliest notational music we have is found on ancient cuneiform tablets called the Hurrian Hymns, dating back to about 1400 BCE, so it took us a little over 3000 years to get to the level of Mozart in the 1700s.

We can give the AI artists a little bit of time to practice. The generative AI art tools, which are very much in their infancy, appear to be allographic arts, and they’re following in their lineage from procedurally generated art has been around for a little while longer. And as an art form in its infancy, there’s still a lot of contested areas.

Whether it counts, the provenance of materials, ethics of where it’s used, all of those things are coming into question. But we’re not going to say that it’s not art, right? And as an art, as work conducted in a new medium, we have certain responsibilities for documenting its use, its procedures, how it’s created.

In the introduction to 2001’s The Language of New Media, Lev Manovich, in talking about the creation of a new media, digital media in this case, noted how there was a lost opportunity in the late 19th and early 20th century with the creation of cinema. Quote, “I wish that someone in 1895, 1897, or at least 1903 had realized the fundamental significance of the emergence of the new medium of cinema and produced a comprehensive record.

Interviews with audiences, systematic account of narrative strategies, scenography, and camera positions as they developed year by year. An analysis of the connections between the emerging language of cinema and different forms of popular entertainment that coexisted with it. Unfortunately, such records do not exist.

Instead, we are left with newspaper reports, diaries of cinema’s inventors, programs of film showings, and other bits and pieces. A set of random and unevenly distributed historical samples. Today, we are witnessing the emergence of a new medium, the meta medium of the digital computer. In contrast to a hundred years ago, when cinema was coming into being, We are fully aware of the significance of this new media revolution.

Yet I am afraid that future theorists and historians of computer media will be left with not much more than the equivalence of the newspaper reports and film programs from cinema’s first decades.” End quote.

Manovich goes on to note that a lot of the work that was being done on computers, especially in the 90s, was stuff prognosticating about its future uses, rather than documenting what was actually going on.

And this is the risk that the denialist framing of AI art puts us in. By not recognizing that something new is going on, that art is being created, and allographic art, we lose the opportunity to document it for the future. And

And as with art, so too with science. We’ve long noted that there’s an incredible amount of creativity that goes into scientific research, that the STEM fields, science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, require and benefit so much from the arts that they’d be better classified as STEAM, and a small side effect of that may mean that we see better funding for the arts at the university level.

But I digress. In the examples I gave earlier of medical research, of AI being used as an assistive technology, we were seeing some real groundbreaking developments of the boundaries being pushed, and we’re seeing that throughout the science fields. Part of this is because of what AI does well with things like pattern recognition, allowing weather forecasts, for example, to be predicted more quickly and accurately.

It’s also been able to provide more assistance with medical diagnostics and imaging as well. The massive growth in the number of AI related projects in recent years is often due to the fact that a number of these projects are just rebranded machine learning or deep learning. In a report released by the Royal Society in England in May of 2024 as part of their Disruptive Technology for Research project, they note how, quote, “AI is a broad term covering all efforts aiming to replicate and extend human capabilities for intelligence and reasoning in machines.”

End quote. They go on further to state that, quote, “Since the founding of the AI field at the 1956 Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, Many different techniques have been invented and studied in pursuit of this goal. Many of these techniques have developed into their own sub fields within computer science, such as expert systems and symbolic reasoning.” end quote.

And they note how the rise of the big data paradigm has made machine learning and deep learning techniques a lot more affordable and accessible, and scalable too. And all of this has contributed to the amount of stuff that’s floating around out there that’s branded as AI. Despite this confusion in branding and nomenclature, AI is starting to contribute to basic science.

A New York Times article published July by Siobhan Roberts talked about how a couple AI models were able to compete at the level of a silver medalist at the recent International Mathematical Olympiad. And this is the first time that the AI model has medaled at that competition. So there may be a role for AI to assist even high level mathematicians to function as collaborators and, again, assistive technologies there.

And we can see this in science more broadly. In a paper submitted to arxiv. org in August of 2024, titled, The AI Scientist Towards Fully Automated Open Ended Scientific Discovery, authors Liu et al. use a frontier large language model to perform research independently. Quote, “We introduce the AI scientist, which generates novel research ideas, writes code, executes experiments, visualizes results, describes its findings by writing a scientific paper, And then runs the simulated review process for evaluation” end quote.

So, a lot of this is scripts and bots and hooking into other AI tools in order to simulate the entire scientific process. And I can’t speak to the veracity of the results that they’re producing in the fields that they’ve chosen. They state that their paper can, quote, “Produce papers that exceed the acceptance threshold at a top machine learning conference as judged by our automated reviewer,” end quote.

And that’s Fine, but it shows that the process of doing the science can be assisted in various realms as well. And in one of those areas of assistance, it’s in providing help for stuff outside the scope of knowledge of a given researcher. AI as an aid in creativity can help explore the design space and allow for the combination of new ideas outside of everything we know.

As science is increasingly interdisciplinary. We need to be able to bring in more material, more knowledge, and that can be done through collaboration, but here we have a tool that can assist us as well. As we talked about with Nessience and Excession a few episodes ago, we don’t know everything. There’s more than we can possibly know, so the AI tools help expand the field of what’s available to us.

We don’t necessarily know where new ideas are going to come from. And if you don’t believe me on this, let me reach out to another scientist who said some words on this back in 1980. Quote, “We do not know beforehand where fundamental insights will arise from about our mysterious and lovely solar system.

And the history of our study of the solar system shows clearly that accepted and conventional ideas are often wrong, and that fundamental insights can arise from the most unexpected sources.” End quote. That, of course, is Carl Sagan. From an October 1980 episode of Cosmos A Personal Journey, titled Heaven and Hell, where he talks about the Velkovsky Affair.

I haven’t spliced in the original audio because I’m not looking to grab a copyright strike, but it’s out there if you want to look for it. And what Sagan is describing there is basically the process by which a Kuhnian paradigm shift takes place. Sagan is speaking to the need to reach beyond ourselves, especially in the fields of science, and the AI assisted research tools can help us with that.

And not just in the conduction of the research, but also in the writing and dissemination of that. Not all scientists are strong or comfortable writers or speakers, and many of them come to English as a second, third, or even fourth language. And the role of AI tools as translation devices means we have more people able to communicate and share their ideas and participate in the pursuit of knowledge.

This is not to say that everything is rosy. Are there valid concerns when it comes to AI? Absolutely. Yes. We talked about a few at the outset and we’ve documented a number of them throughout the run of this podcast. One of our primary concerns is the role of the AI tools in échanger, that replacement effect that happens that leads to technological unemployment.

Much of the initial hype and furor around the AI tools was people recognizing that potential for échanger following the initial public release of ChatGPT. There’s also concerns about the degree to which the AI tools may be used as instruments of control, and how they can contribute to what Gilles Deleuze calls a control society, which we talked about in our Reflections episode last year.

And related to that is the lack of transparency, the degree to which the AI tools are black boxes, where based on a given set of inputs, we’re not necessarily sure about how it came up with the outputs. And this is a challenge regardless of whether it’s a hardware device or a software tool.

And regardless of how the AI tool is deployed, the increased prevalence of it means we’re leading to a soylent culture. With an increased amount of data smog, or bitslop, or however you want to refer to the digital pollution that takes place with the increased amount of AI content in our channels and For-You-Feeds, and this is likely to become even more heightened as Facebook moves to pushing AI generated posts into the timelines.

Many are speculating that this is becoming so prevalent that the internet is largely bots pushing out AI generated content, what’s called the “Dead Internet Theory”, which we’ll definitely have to take a look at it in a future episode. Hint, the internet is alive and well, it’s just not necessarily where you think it is.

And with all this AI generated content, we’re still facing the risk of the hallucinations, which we talked about, holy moly, over two years ago when we discussed the LOAB, that brief little bit of creepypasta that was making the rounds as people were trying out the new digital tools. But the hallucinations still highlight one of the primary issues with the AI tools, and that’s the errors in the results.

In order to document and collate these issues, a research team over at MIT has created the AI Risk Repository. It’s available at airisk. mit. edu. Here they have created taxonomies of the causes and domains where the risks may take place. However, not all of these risks are equal. One of the primary ones that gets mentioned is the energy usage for AI.

And while it’s not insignificant, I think it needs to be looked at in context. One estimate of global data center usage was between 240 and 340 terawatt hours, which is a lot of energy, and it might be rising as data center usage for the big players like Microsoft and Google has gone up by like 30 percent since 2022.

And that still might be too low, as one report noted that the actual estimate could be as much as 600 percent higher. So when you put that all together, that initial estimate could be anywhere between a thousand and 2000 terawatts. But the AI tools are only a fraction of what goes on at the data centers, which include cloud storage and services, streaming video, gaming, social media, and other high volume activities.

So you bring that number right back down. And AI is using? The thing is, whatever that number is, 300 terawatts times 1. 3 times six divided by five. Whatever that result ends up being doesn’t even chart when looking at global energy usage. Looking at a recent chart on global primary energy consumption by source over at Our World in Data, we see that the worldwide consumption in 2023 was 180, 000 terawatt hours.

The amount of energy potentially used by AI hardly registers as a pixel on the screen compared to worldwide energy usage that were presented with the picture in the media where AI is burning up the planet. I’m not saying AI energy usage isn’t a concern. It should be green and renewable. And it needs to be verifiable, this energy usage of the AI companies, as there is the risk of greenwashing the work that is done, of painting over their activities true energy costs by highlighting their positive impacts for the environment.

And the energy usage may be far exceeded by the water usage that’s used for the cooling of the data centers. And as with the energy usage, the amount of water that’s actually going to AI is incredibly hard to dissociate from all the other activities that are taking place in these data centers. And this greenwashing, which various industries have long been accused of, might show up in another form as well.

There is always the possibility that the helpful stories that are presented, AI tools have provided for various at risk and minority populations, are presented as a form of “aidwashing”. And this is something we have to evaluate for each of the stories posted in the AI Positivity Archive. Now I can’t say for sure that “aidwashing” specifically as a term exists.

A couple searches didn’t return any hits, so you may have heard it here first. However, while positive stories about AI often do get touted, do we think this is the driving motivation for the massive investment we’re seeing in the AI technologies? No, not even for a second. These assistive uses of AI don’t really work with the value proposition for the industry, even though those street uses of technology may point the way forward in resolving some of the larger issues for AI tools with respect to resource consumption and energy usage.

The AI tools used to assist Casey Harrell, the ALS patient mentioned near the beginning of the show, use a significantly smaller model than one’s conventionally available, like those found in ChatGPT. The future of AI may be small, personalized, and local, but again, that doesn’t fit with the value proposition.

And that value proposition is coming under increased scrutiny. In a report published by Goldman Sachs on June 25th, 2024, they question if there’s enough benefit for all the money that’s being poured into the field. In a series of interviews with a number of experts in the field, they note how initial estimates about both the cost savings, the complexity of tasks that AI is available to do, and the productivity gains that would derive from it, are all much lower than initially proposed or happening on a much longer time frame.

In it, MIT professor Daron Acemoglu forecasts minimal productivity and GDP growths, around 0. 5 percent or 1%, whereas Goldman Sachs predictions were closer to 9 percent and 6 percent increase in GDP. With such varying degrees of estimates, what the actual impact of AI in the next 10 years is, is anybody’s guess.

It could be at either extreme or somewhere in between. But the main takeaway from this is that even Goldman Sachs is starting to look at the balance sheet and question the amount of money that’s being invested in AI. And that amount of money is quite large indeed.

In between starting recording this podcast episode and finishing it, OpenAI raised 6. 6 billion dollars in a funding round from its investors, including Microsoft and Nvidia, which is the largest ever recorded. As reported by Reuters, this could value the company at 157 billion dollars and make it one of the the world. valuable private companies in the world. And this coincides with the recent restructuring from a week earlier which would remove the non profit control and see it move to a for profit business model.

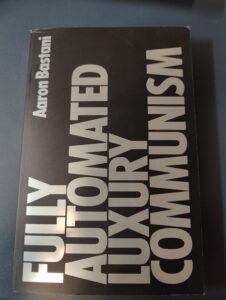

But my final question is, would this even work? Because it seems diametrically opposed to what AI might actually bring about. If assistive technology focused on automation and Echange, then the end result may be something closer to what Aaron Bastani calls “fully automated luxury communism”, where the future is a post-scarcity environment that’s much closer to Star Trek than it is to Snow Crash.

How do you make that work when you’re focused on a for profit model? The tool that you’re using is not designed to do what you’re trying to make it do. Remember, “The street finds its own uses for things”, though in this case that street might be Wall Street. The investors and forecasters at Goldman Sachs are recognizing that disconnect by looking at the charts and tables in the balance sheet.

But their disconnect, the part that they’re missing, is that the driving force towards AI may be one more of ideology. And that ideology is the California ideology, a term that’s been floating around since at least the mid 1990s. And we’ll take a look at it next episode and return to the works of Lev Manovich, as well as Richard Barbrook, Andy Cameron, and Adrian Daub, as well as a recent post by Sam Altman titled ‘The Intelligence Age’.

There’s definitely a lot more going on behind the scenes.

Once again, thank you for joining us on the Implausipod. I’m your host, Dr. Implausible. You can reach me at drimplausible at implausipod. com. And you can also find the show archives and transcripts of all our previous shows at implausipod. com as well. I’m responsible for all elements of the show, including research, writing, mixing, mastering, and music.

And perhaps somewhat surprisingly, given the topic of our episode, no AI is used in the production of this podcast. Though I think some machine learning goes into the transcription service that we use. And the show is licensed under Creative Commons 4. 0 share alike license. You may have noticed at the beginning of the show that we described the show as an academic podcast and you should be able to find us on the Academic Podcast Network when that gets updated.

You may have also noted that there was no advertising during the program and there’s no cost associated with the show. But it does grow from word of mouth of the community. So if you enjoy the show, please share it with a friend or two, and pass it along. There’s also a buy me a coffee link on each show at implausopod.

com, which will go to any hosting costs associated with the show. I’ve put a bit of a hold on the blog and the newsletter, as WordPress is turning into a bit of a dumpster fire, and I need to figure out how to re host it. But the material is still up there, I own the domain. It’ll just probably look a little bit more basic soon.

Join us next time as we explore that Californian ideology, and then we’ll be asking, who are Roads for? And do a deeper dive into how we model the world. Until next time, take care and have fun.

Bibliography

A bottle of water per email: The hidden environmental costs of using AI chatbots. (2024, September 18). Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2024/09/18/energy-ai-use-electricity-water-data-centers/

A Note to Our Community About our Comments on AI – September 2024 | NaNoWriMo. (n.d.). Retrieved October 5, 2024, from https://nanowrimo.org/a-note-to-our-community-about-our-comments-on-ai-september-2024/

Advances in Brain-Computer Interface Technology Help One Man Find His Voice | The ALS Association. (n.d.). Retrieved October 5, 2024, from https://www.als.org/blog/advances-brain-computer-interface-technology-help-one-man-find-his-voice

Balevic, K. (n.d.). Goldman Sachs says the return on investment for AI might be disappointing. Business Insider. Retrieved October 5, 2024, from https://www.businessinsider.com/ai-return-investment-disappointing-goldman-sachs-report-2024-6

Broad, W. J. (2024, July 29). Artificial Intelligence Gives Weather Forecasters a New Edge. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/07/29/science/ai-weather-forecast-hurricane.html

Card, N. S., Wairagkar, M., Iacobacci, C., Hou, X., Singer-Clark, T., Willett, F. R., Kunz, E. M., Fan, C., Nia, M. V., Deo, D. R., Srinivasan, A., Choi, E. Y., Glasser, M. F., Hochberg, L. R., Henderson, J. M., Shahlaie, K., Stavisky, S. D., & Brandman, D. M. (2024). An Accurate and Rapidly Calibrating Speech Neuroprosthesis. New England Journal of Medicine, 391(7), 609–618. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2314132

Consumers Know More About AI Than Business Leaders Think. (2024, April 8). BCG Global. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2024/consumers-know-more-about-ai-than-businesses-think

Cosmos. (1980, September 28). [Documentary]. KCET, Carl Sagan Productions, British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC).

Donna. (2023, October 9). Banksy Replaced by a Robot: A Thought-Provoking Commentary on the Role of Technology in our World, London 2023. GraffitiStreet. https://www.graffitistreet.com/banksy-replaced-by-a-robot-a-thought-provoking-commentary-on-the-role-of-technology-in-our-world-london-2023/

Gen AI: Too much spend, too little benefit? (n.d.). Retrieved October 5, 2024, from https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/top-of-mind/gen-ai-too-much-spend-too-little-benefit

Goodman, N. (1976). Languages of Art (2 edition). Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Goodman, N. (1978). Ways Of Worldmaking. http://archive.org/details/GoodmanWaysOfWorldmaking

Hill, L. W. (2024, September 11). Inside the Heated Controversy That’s Tearing a Writing Community Apart. Slate. https://slate.com/technology/2024/09/national-novel-writing-month-ai-bots-controversy.html

Hu, K. (2024, October 3). OpenAI closes $6.6 billion funding haul with investment from Microsoft and Nvidia. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/technology/artificial-intelligence/openai-closes-66-billion-funding-haul-valuation-157-billion-with-investment-2024-10-02/

Hu, K., & Cai, K. (2024, September 26). Exclusive: OpenAI to remove non-profit control and give Sam Altman equity. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/technology/artificial-intelligence/openai-remove-non-profit-control-give-sam-altman-equity-sources-say-2024-09-25/

Knight, W. (n.d.). An ‘AI Scientist’ Is Inventing and Running Its Own Experiments. Wired. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://www.wired.com/story/ai-scientist-ubc-lab/

LaBossiere, M. (n.d.). AI: I Want a Banksy vs I Want a Picture of a Dragon. Retrieved October 5, 2024, from https://aphilosopher.drmcl.com/2024/04/01/ai-i-want-a-banksy-vs-i-want-a-picture-of-a-dragon/

Lu, C., Lu, C., Lange, R. T., Foerster, J., Clune, J., & Ha, D. (2024, August 12). The AI Scientist: Towards Fully Automated Open-Ended Scientific Discovery. arXiv.Org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.06292v3

Manovich, L. (2001). The language of new media. MIT Press.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. The New American Library.

Mickle, T. (2024, September 23). Will A.I. Be a Bust? A Wall Street Skeptic Rings the Alarm. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/23/technology/ai-jim-covello-goldman-sachs.html

Milman, O. (2024, March 7). AI likely to increase energy use and accelerate climate misinformation – report. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/mar/07/ai-climate-change-energy-disinformation-report

Mueller, B. (2024, August 14). A.L.S. Stole His Voice. A.I. Retrieved It. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/14/health/als-ai-brain-implants.html

Overview and key findings – World Energy Investment 2024 – Analysis. (n.d.). IEA. Retrieved October 5, 2024, from https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2024/overview-and-key-findings

Roberts, S. (2024, July 25). Move Over, Mathematicians, Here Comes AlphaProof. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/25/science/ai-math-alphaproof-deepmind.html

Schacter, R. (2024, August 18). How does Banksy feel about the destruction of his art? He may well be cheering. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/aug/18/banksy-art-destruction-graffiti-street-art

Science in the age of AI | Royal Society. (n.d.). Retrieved October 2, 2024, from https://royalsociety.org/news-resources/projects/science-in-the-age-of-ai/

Sullivan, S. (2024, September 25). New Mozart Song Released 200 Years Later—How It Was Found. Woman’s World. https://www.womansworld.com/entertainment/music/new-mozart-song-released-200-yaers-later-how-it-was-found

Taylor, C. (2024, September 3). How much is AI hurting the planet? Big tech won’t tell us. Mashable. https://mashable.com/article/ai-environment-energy

The AI Risk Repository. (n.d.). Retrieved October 5, 2024, from https://airisk.mit.edu/

The Intelligence Age. (2024, September 23). https://ia.samaltman.com/

What is NaNoWriMo’s position on Artificial Intelligence (AI)? (2024, September 2). National Novel Writing Month. https://nanowrimo.zendesk.com/hc/en-us/articles/29933455931412-What-is-NaNoWriMo-s-position-on-Artificial-Intelligence-AI

Wickelgren, I. (n.d.). Brain-to-Speech Tech Good Enough for Everyday Use Debuts in a Man with ALS. Scientific American. Retrieved October 5, 2024, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/brain-to-speech-tech-good-enough-for-everyday-use-debuts-in-a-man-with-als/