(This was originally released as Implausipod Episode 25, on January 2, 2024)

https://www.implausipod.com/1935232/14232183-implausipod-e0025-echanger

[buzzsprout episode=’14232183′ player=’true’]

Échanger

Bonjour. J’ai une question à vous poser. Voulez vous échanger avec moi? Really? Are you sure? That’s fantastic! Because sometimes the English language doesn’t have the right word that does exactly what you need it to do, that expresses the entirety of what you’re looking for. And in this case, that word, échanger, is what we’re going to use when we’re talking about automation.

I’ll explain more in this episode of The Implausipod.

Welcome to The Implausipod, a podcast about the intersection of art, technology, and popular culture. I’m your host, Dr. Implausible. And in this episode, we’re going to take a look at part three of our two part series on the sphere in Las Vegas. Yeah, things got out of hand. And follow through on an observation that dominated the discourse in 2023 and serves to be at the forefront of our discussion about technology in 2024 and beyond.

And that concept is échanger.

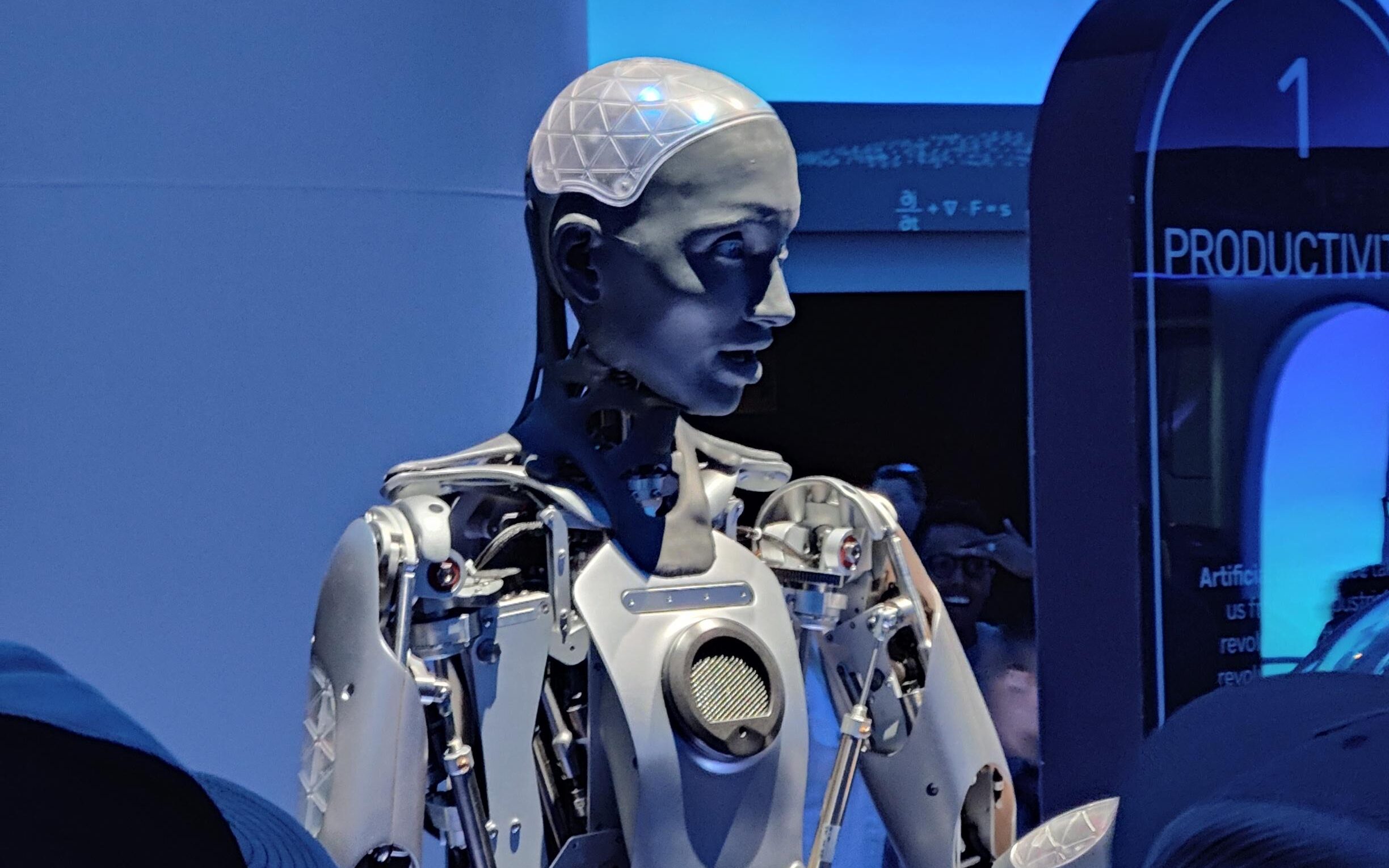

So I mentioned this the other episode when we were looking at the Sphere in Las Vegas and how it had a lot of workers that were doing fairly regular rote tasks, like holding up signs and directing traffic. And as they funneled everybody into the entrance of the Sphere, into the first floor of that massive auditorium, We met the robots, the auras, that were doing almost exactly the same thing:

responding to the crowd, answering questions of the audience, and directing them. But responding to them personally. And it struck me at the time, especially as we were kind of going through and looking at five different Auras, the sisters, that were explaining what we saw in each of these stations, that each of them could do the job of the others, their human chaperones, without too much more training.

It was job replacement made real. And this is where I started to look for a term that can kind of encompass that. Now, it’s something that’s been discussed a whole lot, that idea of job loss through automation, and it’s accelerated in the last year since the release of ChatGPT and the other AI assisted art tools or large language models, as people are worried that that’s going to directly lead to job loss.

But that’s only one part of the story, as there’s also things like the development of the Boston Dynamics robots, and other robotic assisted tools that are taking the roles of persons, and dogs, and mules within various environments. And so we have this assemblage of different things that are all connected to this job loss.

And in order to encompass these factors, I found myself stumbling for a word. I recalled back to some of my training in grad school where we were looking at the idea of actor network theory and the author Michael Callon. In 1986, he came up with the idea of interessement, And obviously he was French, but in his work titled Some Elements of the Sociology of Translation, he was talking about that shift that took place, and he was using the French language to describe it, a specific instance.

So I thought I’d reach out and draw on that inspiration, and see if perhaps a verb in French could encompass what we are seeing within the world at large. Hence, Échanger. And I like it. It works. I know there’s been some other authors who have used other verbs to describe different processes within the tech sphere lately, and sometimes those will get caught by language filters and sometimes they won’t, but I think Échanger, with all its multiplicity of meanings, adequately captures the breadth of what we’re looking for here when we’re talking about automation, agentrification via AI tools, and virtualization,

and what they might mean for workers that are working alongside machines that will replace them. That’s what the term means, or what it means now in the context of this episode, and in my reference to technological replacement. And speaking from a personal perspective, I have more than just an academic interest in echange.

I’ve been automated out of jobs on at least a couple different occasions over the last 30 years, and I’ve experienced outsourcing from a worker perspective on a couple occasions as well. And in some cases, both at the same time. For example, in one of those instances, I was working for a local tech company that was manufacturing phone handsets.

And there was seven people working on the assembly line, and after a few months, they brought in one machine that could replace the role of one of the persons on the line. And our duty was to feed material into the machine. And then after that was tested and worked out, within a month, they brought in another one.

And slowly, that team of seven was whittled down to two, as we’d just really need somebody at the front end to load the parts, and at the back end to take out the manufactured ones and test them. And it ran pretty much 24 7. And after they had fine tuned that, they packed up the whole factory and shipped it down to Mexico.

So we had both replacement, échanger, and outsourcing happening within the same instance. Now, obviously, this isn’t anything new, it’s been happening for years. The term technological unemployment was originally proposed by Keynes and included in his Essays in Persuasion from 1931, and has been returned to many times since, including by Nobel Prize winner Wassily Leontief in his paper titled Is Technological Unemployment Inevitable?

Daniel Suskind writes in his 2020 book, A World Without Work, that there can be two kinds of technological unemployment, frictional and structural. Frictional tech unemployment is that kind that is imposed by switching costs and not all workers being able to transition to the new jobs available in the changed economy.

The friction prevents the workers from moving as freely as needed. And this is what was happening in my experience with the jobs where échanger occurred. I want to be clear, a lot of those jobs that I was automated out of were not great. It was hard, demanding work, or physical work that was replaced by labor saving devices, in this case, machines.

But it still meant a job loss, and there was one less role, or entry level role, for a high school student, or college student, or casual worker, or whatever I was at the time.

Échanger. (part 2)

And that’s part of the problem. On March 27th, 2023, the Economics Research Department at Goldman Sachs released a report titled The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth, otherwise known as the Briggs-Kodnani Report. The report was published several months after the release of ChatGPT4 to the general public and captures the fear that was seen during its initial wave of use.

The report focuses on the economic impacts of generative AI and its ability to create content that is, quote, indistinguishable from human created outputs and breaks down communication barriers, end quote, and speculates what the macroeconomic effects of a large scale rollout of such technology would be.

Now, the authors state that this large scale introduction of AI tools would be, or Could be a significant disruption to the labor market. The authors take a look at occupational tasks on jobs, and using standard industry classifications, they find that approximately two thirds of current jobs are exposed to some degree of AI automation.

And the generated AI could, quote, substitute up to one fourth of current work. Now, if you take those estimates, like they did, it means it could expose something like 300 million full time jobs to automation through AI, or what I like to call agentrification. And that’s over a 10 year period. This would create an incredible amount of churn in the workforce, and whenever we hear about churn, we need to consider the human costs behind those terms.

A lot of people will lose their jobs, and well, the Schumpeterian creative destruction generally means that people get new jobs, or that old workers that haven’t moved become more productive, as a study by David Autor and others from 2022 found when they looked at U. S. census data from 1940 to 2018. and found that 60 percent of workers in 2018 were working at jobs that did not exist in 1940, and that most of this growth is fueled by technology driven job creation.

But there’s usually a lag between the two, between losing one job and having tech create new positions, the frictional tech unemployment we mentioned earlier. But there could also be more, the second kind mentioned above, structural technological unemployment. As stated by Briggs and Kodnani, there could very well be just some permanent job losses, and that can be a challenge for us to address as a society.

Now, with the productivity growth, Briggs and Kodnani argue we could see a 1. 5 percent growth over a 10 year period following widespread adoption, so the timing for all of this is actually quite distant. Everybody’s thinking everything’s going to end immediately, and that’s not necessarily the case. But it sure can feel like it’s coming around the corner right away.

The authors also estimated that GDP globally could increase by 7%, but that would depend on a whole lot of factors, so I’d like to bracket off that prediction, as there’s too many variables involved. The two things I really found interesting about their report was a, the timescale that they’re looking at this and B, the specific jobs that they’re looking at.

So, as I said, the ability to predict the specific GDP on something as large scale as this across the economy on a 10 year timeframe is just like, let’s not do that. It’s just. There, you can put numbers into it, but I think there’s just far too much speculation involved in actually being able to get to that level of precision with anything.

The interesting thing in the paper was their estimate of the work tasks that could be automated in the industries that could be more significantly affected. There’s two key charts for this. It’s Exhibit 5, which is the share of industry employment exposed to automation, and Exhibit 8, which is the share of industry employment by relative exposure to automation by AI.

And there’s some of these that are, you’re not going to see any automation improvements in. Some industries are just not really going to take a hit. But some of them could have AI as a complement, and some of them will have AI as a replacement. And this is in Exhibit 8, and I think this is probably the most interesting thing in the whole article.

The thing the Briggs and Kodnani report captures is a lot of the public’s initial impressions of OpenAI, and of ChatGPT as well. This drove some of the furor because as people were able to access the tool and use it, one of the things they’d naturally do is go, Well, does this help me? Can I use this for my own job?

And B, how well does this do my own job? So a lot of the initial uproar and the impacts from ChatGPT was people using it to see how it would do their job and being concerned with what they saw. So I think a lot of their concerns and fears are well founded. If you’re doing basic coding tasks, and the tool is able to replicate some of those tasks fairly simply, you’re like, oh my god, what’s going on?

If you’re doing copywriting or any of those roles that receive a significant amount of replacement, as in the Table 8 on the Report, like office and administrative support, and legal, you know, traditionally one of those things we didn’t really think would be automated, you’re going to have some serious concerns.

Martin Ford’s book, The Rise of the Robot, talks about that white collar replacement, where we’re seeing job loss and automation in roles that traditionally hadn’t seen it before. When we think of échanger. When we think of automation, we think of it as, like, large industrial machinery. We’re thinking of things like factory machines, being able to produce something that a craftsman might have had to work at for long hours, but able to do that at an industrial scale

or rapid scale. And this change has us going all the way back to the era of the Luddites in the early industrial revolution in England. Now, when ChatGPT launched, we’re starting to see the process of what I like to call agentrification, tech replacement through AI tools. And basically, we’re having automation of white collar work in things like the legal field.

I mean, this might fly under the radar for a lot of academic analysis, but if you’re paying attention to what gets advertised, there were signs. Tools like LegalZoom were continually advertised on the Jim Rome sports talk show over a decade ago, and we note that being able to be centralized and outsourcing that work would indicate that there’s, you know, some risks of échanger involved in those particular fields.

Now, there’s other fields where this white collar work is at the risk of echangér as well. The Hollywood Strikes of 2023 had similar motivations. Though their industries were moving quicker to roll out the tools, being on the forefront of their use, the Actors Guild and the Writers Guild were much more proactive against the tools because they saw the role that would take place in their replacement.

Given the role of the cultural industries, like movie production, being at the leading edge of soft innovation, we were already seeing digital de-aging tech and reinsertion in major motion pictures, notably from Disney properties like Star Wars with both Peter Cushing and Carrie Fisher, whose likenesses were used in films after they had passed away, and the de aging of Harrison Ford in Indiana Jones 5.

This leads to an interesting question. Can Échanger lead to a replacement of you with your younger self? I don’t know. Let’s explore that a bit more, next.

Échanger (part 3)

On December 2nd, 2023, the rock band KISS played their final show at Madison Square Gardens. Now, this may have not been newsworthy, as they had been doing Last show ever since late last century, but as the members were now in their 70s, there was a feeling that they really meant it this time. However, at the end of the show, they revealed that they weren’t quite done just yet, and they unveiled their quote unquote immortal digital avatars that will represent the band on stage in the future.

Now, KISS aren’t the first in doing this by any means. The Swedish pop band ABBA has been doing this for a while, and Kiss contacted the same company, Pop House Entertainment, to work on their avatars. Now, Bloomberg News reports that the ABBA shows are pulling in 2 million a week. Yes, you heard that correctly.

Clearly, I’m in the wrong business. But this trend to virtual entertainers has been happening for a while. When a hologram Tupac appeared with Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre at Coachella in 2012, it was something that had already been in the works. Bands like Gorillaz and Death Clock had long used virtual or animated avatars, and within countries like South Korea, virtual avatars are growing in popularity as well, like M.A.V.E., the four member virtual K pop group that’s been moving up the charts in 2023. We noted a few episodes ago that one of the challenges for 21st century entertainment complexes like the Sphere is providing enough continuous content, and virtualized groups like this may well be able to fill that role and allow the Sphere to provide content worldwide by having virtual avatars that can fill the entire space in ways that Bono and the Edge on a small stage in front of a massive screen can’t quite do. And more than just this, the shift to remote that’s happened as part of the pandemic response could mean this technology could be rolled out in education and other fields as well.

So we’re just seeing the thin edge of the wedge of this virtualization component of Échanger. With large companies like Apple and Meta continually pushing the Metaverse, we’re going to see more and more of it in the coming years. So 2024 may well be the year of virtualization. We’ll dive further into virtualization and the Metaverse in upcoming weeks here on the Implausipod.

Why échanger? (part 4)

Well, basically it covers three things. We’ve kind of discovered it covers automation, which is the industrial process that we’ve been seeing for centuries now. It covers virtualization, the shift to digital in entertainment, education, conferences, and distribution. And the third thing it covers is agentrification, the replacement of workers or roles or jobs by AI.

So, this is different than outsourcing, as outsourcing may work in conjunction with some of the above, as noted in my own personal experience earlier, and these are all metaprocesses of the trends towards technological unemployment. If we look at any of these, automation, Virtualization and agentification, they’re all metaprocesses of translation.

Now, the work I mentioned earlier by Michel Callon, in Some Elements Towards the Sociology of Translation from 1986, is basically talking about that, describing what we call a flat ontology. An ontology, in this case, is a way of describing the world. And what a flat ontology does is it treats the actors in the world as similar.

So, normally, when we talk about an ontology, we’re talking about like with like, right? We’re talking about people, or we’re talking about things, or we’re talking about institutions, firms, we’re looking at things on the same level. When we flatten the ontology, we treat all the actors or agents in the system equally, and we can look at the power relations between them.

We use the same terms for the actors, so in this case, it would mean human and non human actors are treated in the same way. We treat the things the same as the people. That doesn’t necessarily mean we treat the people as things, but we say that everything here has to be described with the same terms when it comes to their agency.

This is what interessment means. That’s the agency. In between state, the interposition, when Michel Callon is talking about translation between asymmetrical actors, it’s that moment where we connect dissimilar things. And so this is where we come into the idea of échanger as a metaprocess for these three trends of replacement.

And that’s why we chose échanger for this process of translation as well. Échanger is a process of translation of a different kind. Échanger is the metaprocess of having something different do the job or being a replacement for the task. So if échanger means in French, literally a trade and exchange, a swap, then we’re extending or exapting the term a little bit in this case, where to us échanger means replacement in place.

So if we return to our example from the Sphere in Las Vegas, we can see this happening with the Auras and the workers. The role is similar, but it’s a different agent, different actor that is taking that place. This is what we see with virtualization as well, or automation, the agentrification that’s taking place due to AI.

And sometimes those machines, those tools, those devices, means the job of many can be done by one. But it also means that the one still occupies the same place within the network of tasks and associations within the process around it. Think of those machines embedded in the assembly line I mentioned earlier.

Where the staff went down from 7 to 2 and the production line was turned into a black box with inputs and outputs. But what’s actually going on in that black box? We can have some questions. With some automated processes, we can tell. But with AI tools, we don’t necessarily know. And that can be a significant problem. Especially when we’re facing Échanger.

Bibliography:

Autor, D., Chin, C., Salomons, A. M., & Seegmiller, B. (2022). New Frontiers: The Origins and Content of New Work, 1940–2018 (Working Paper 30389). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w30389

Hatzius, J. et al. (2023)The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth . (Briggs/Kodnani). Retrieved December 5, 2023,

Ford, M. (2016). The Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of Mass Unemployment. Oneworld Publications.

Leontief, W. (1979). Is Technological Unemployment Inevitable? Challenge, 22(4), 48–50.

Susskind, D. (2020). A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How We Should Respond. Metropolitan Books.

They’re not human? AI-powered K-pop girl group Mave: eye global success. (2023, March 17). South China Morning Post.

Tupac Coachella hologram: Behind the technology – CBS News. (2012, November 9).